Making Presence

2018

The third in a three-part series of concurrent investigations into creative work and critical dialogue, MAKING PRESENCE is a text developed in conjunction with Specific Objects and Species of Spaces. The aim of the text is to explore ideological issues relating to creative practice and to articulate the motivations of current architectural offices with reference to the processes and work undertaken in Specific Objects and Species of Spaces. Themes to be discussed are presence, atmosphere, history, aesthetics, epistemology, and interdisciplinarity as an alternative to traditional architectural practice.

The essay is an inquiry into quality, process, and critique.

Specific Objects | Species of Spaces | MAKING PRESENCE

2018

The third in a three-part series of concurrent investigations into creative work and critical dialogue, MAKING PRESENCE is a text developed in conjunction with Specific Objects and Species of Spaces. The aim of the text is to explore ideological issues relating to creative practice and to articulate the motivations of current architectural offices with reference to the processes and work undertaken in Specific Objects and Species of Spaces. Themes to be discussed are presence, atmosphere, history, aesthetics, epistemology, and interdisciplinarity as an alternative to traditional architectural practice.

The essay is an inquiry into quality, process, and critique.

Specific Objects | Species of Spaces | MAKING PRESENCE

The following essay was written in Spring 2018 as part of an independent terminal studio for Master of Architecture coursework at The University of Texas at Austin under the guidance of professors Michael Benedikt and David Heymann.

Making Presence

What is “present” to us (very much in the sense of the Latin form prae-esse) is in front of us, in reach of and tangible for our bodies [...]. If producere means, literally, “to bring forth,” “to pull forth,” then the phrase “production of presence” would emphasize that the effect of tangibility that comes from the materialities of communication is also an effect in constant movement. In other words, to speak of “production of presence” implies that the (spatial) tangibility effect coming from the communication media is subjected, in space, to movements of greater or lesser proximity, and of greater or lesser intensity.

Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, The Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey1

Visual art embraces a different form of research strikingly described during one of the first European conferences on artistic research by Sarat Maharaj as “spasmodic, interdisciplinary probes, haphazard cognitive investigations, dissipating interaction, and imaginary archiving.”a A mode of research not focused purposefully on generating “expert knowledge”, but specifically on expressing experiential knowledge. Such knowledge cannot be channeled through rigid academic scientific guidelines of generalization, repetition and quantification, but requires full attention for the unique, the qualitative, the particular, and the local. In short, a form of nominal knowledge production unable to serve a retinal, one-dimensional worldview characterized by transparent singularity, but rather creating – and if necessary demanding – room for the undefined, the heterogeneous, the plural, the contingent, and the relative. Such knowledge production can only be the sole outcome of a research practice defined at all times by an absolutely open, non-disciplinary attitude and an insertion of multiple models of interpretation.

Henk Slager, Nameless Science2

1 Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich. 2004. Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, p. 17.

2 Slager, Henk. 2009. “Nameless Science.” MaHKUzine: Journal of Artistic Research (Utrecht Graduate School of the Visual Art and Design).

a Sarat Maharaj, Unfinishable Sketch of ‘An Object in 4D’ Scenes of Art Research in Annette W. Balkema and Henk Slager, Artistic Research, Amsterdam/New York, 2004, p. 50

CREATIVE CAUSALITY

In the final essay of my undergraduate education in architecture I wrote about the values and processes that I had cultivated through my studio work in the preceding five years. The essay, entitled My Architecture, began under the premise that it would communicate something about my methodology of designing, but it ended up in a place I did not expect. The final three sentences read:

In the final essay of my undergraduate education in architecture I wrote about the values and processes that I had cultivated through my studio work in the preceding five years. The essay, entitled My Architecture, began under the premise that it would communicate something about my methodology of designing, but it ended up in a place I did not expect. The final three sentences read:

My architecture still comes from places I cannot always locate. Then again, if we imbue our work with aspects of our own identities, it won’t matter how we work. What will matter instead is what we make and what it says about us.3

3 Mahaffey, Max. 2010. “My Architecture.” DATUM: Student Journal of Architecture 67-71.

These few sentences are perhaps the best way to begin the final essay of my graduate education - one that attempts to clarify the current state of design and architecture in relation to the aesthetic and ethical theories that continue to guide my work from the shadows. It is my hope that these words can sufficiently bring to light a sensibility that I believe has the best potential to produce work of a quality worth aspiring toward. In re-reading those words it became evident that even back then I knew the importance of doing work in contrast to speaking about it. But underneath that was an acceptance that the dialogue about the work that was produced is what enriches the work with the vitality to stand on its own; it is because a conversation is being had about it that it holds onto some sense of autonomy, and thus its right to existence. Herein lies the dilemma to act towards the work as simultaneously its creator, its critic, and its user.

The foolhardy portion of my text is the implication that imbuing our work with aspects of our own identities is an active measure when it is actually merely a natural (and inevitable) aspect of doing the work. The only fundamentally unique thing any of us have to offer to each other and to the world at large, is our own point of view. That is, the thoughts, feelings, expressions, creations, etc... the work we do; the act or gesture. The product is an amalgam of the particular act and the culture and context to which the actor belongs that underlies the ideas behind the work. Milan Kundera writes,

Without the slightest doubt, there are far fewer gestures in the world than there are individuals. That finding leads us to a shocking conclusion: a gesture is more individual than an individual. We could put it in the form of an aphorism: many people few gestures [...] a gesture cannot be regarded as the expression of an individual as his creation (because no individual is capable of creating a fully original gesture, belonging to nobody else), nor can it even be regarded as that person’s instrument; on the contrary, it is gestures that use us as their instruments, as their bearers and incarnations.4

4 Kundera, Milan. 1988. Immortality. Translated by Peter Kussi. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

It is taken here as a given that we are beings embedded in a culture, which in turn informs our thinking and feeling without realizing it. The act/gesture is a form of interpretation on the part of the actor/creator that embodies the culture and the individual simultaneously, but whose particular durational doing is the unique contribution. With this belief - and the understanding that beliefs change as we adapt to new information and changing times - it is evident that the infinite number of circumstances under which a person arrives to the moment when he/she must contribute his/her point of view gives way to the conviction that things and events are infinitely interpretable. The quality of the work, not the originality, remains the central issue. First posited by the creator/designer within his/her gesture, the quality is substantiated by the quantity and thoughtfulness of subsequent interpretations. Although an objective measure of quality is ignorant on behalf of the believer and presumptuous on the part of its arbiter, working towards some quality still seems to be the most sensible goal. Quality is a good idea well executed.5 The works of any art or architecture that we regard as “timeless” may actually only be those works which inspire the richest interpretations over time.

The irony of creative achievement is that in discussion of the work, society expects an outline of the meaning of a work to come from the artist/creator; following this explanation a critical determination is made of the work’s quality. I suspect a closer reality is that the quality of the piece is first determined by the artist, who puts the work out into the world; and thereafter the spectators (critics and laypeople alike) derive their own meanings. This is not to suggest that the creator is absolved the responsibility of communicating about his/her intentions, influences, or references, but the work ultimately must stand on its own, segregated from a narrative that the majority of people will not or cannot access, and part of a context which provides it with endless routes for interpretation. The issues in question have to do with how explicit the creator must be about his/her intentions for the work and the qualitative determination of the effects of the work.

When the work in question functions as a service – as in the majority of designer/client relations – the creator must be inordinately explicit about what he/she believes the work will do and why so that the client may approve the work. The work is on the clients’ terms because it is a service they are paying for. The rare exception of this dynamic is when a client and designer have a creative rapport which ensures an alignment of goals and intentions – many of which can remain unspoken. This relationship is built upon a foundation of trust that is rooted in an understanding of and commitment toward the kind of work the creator has previously demonstrated. It is the creator’s responsibility to communicate that the types of work he/she advocates for is not an active measure of expressing internal thoughts/feelings, but an expression of a point of view that is still unique to the designer but is substantiated by the ways in which the decisions relate to a subjugation of the creator’s ego. This point is important because it is not the active imposing of a designer’s will that ensures the product will resonate with the designer’s sensibilities, but rather a process that subdues definitive value judgments on the designer’s part which strips the process as much as possible of the designer’s overt biases because the product will reveal them all the same. It is a difference between shouting and speaking casually. This neutrality of expression facilitates a nonlinear process in which the type of intention that should be fostered by the designer deals directly with work’s future presence, and only informs the process up until the point of completion, at which point the agency of the artist/designer is revoked as the sole authority, for now it belongs to the user and critics as much the creator. But the values that inform each of those three roles are fluid and in considering the value of art in terms of its ability to communicate its clear meaning directly, Leo Steinberg offers his canonical interpretation of Jasper Johns: “And is this finally what the picture means? No, not that at all. Who would need pictures if they were that translatable? What I am saying is that Johns puts two flinty things in a picture and makes them work against one another so hard that the mind is sparked. Seeing them becomes thinking.”6 The work communicates something that language always fails to sufficiently address, so we require being co-present with it to reckon with its additional qualities.

But the relationship of what is consequent from what was intended is not so causal as to elicit comprehensive effects of meaning, and therefore undoes the authority of the designer by separating the initial act from its outcome. The goal, really, is to develop an autonomous body of work that stands on its own, separate from the designer’s intentions, critical dialogue, pre-determined meaning, or post-rationalizations. As its own subject, the resultant work communicates something, both linguistically (meaning effects) and non-linguistically (presence effects) about itself and implies additional qualities about its creator and its context; but what it may explain about the intentions of the creator may be limited. In aphorism 112 of his seminal work The Gay Science, Friedrich Nietzsche exposes the limitations of a cause/effect duality:

5 It is perhaps best to leave this definition as it is, with a latitude and suggestiveness to remain agreeable. Still a couple qualifications are worth noting. First, the inextricable link between the execution (workmanship) and the idea (motivation) is crucial to form a basis for quality. Craft or workmanship of risk, considers the ideas behind the work as principally part of the adjudication of quality, though neither the idea nor the workmanship can retain autonomous value in a conversation of quality. The well-made tool is praised for its craft, but does not inspire interpretation about its relation to us. Similarly though, much of the art of the 1960’s that could be categorized under the Minimalism umbrella claimed no deftness of skill to be responsible for its quality. This notion of workmanship is baked into the idea before the work has even entered the world – it is not a skirting around of the importance of craft, but a relationship which is constantly there. Le Corbusier’s work in India, Francis Keré’s work in Burkina Faso, and Pezo Von Ellrichshausen’s work in Chile cannot assume some objective measure of workmanship because it is simply inaccessible in those societies. But the ideas and motivations behind the work remain intact because they recognize that the workmanship is one of risk and the work finds its value in negotiating the limits of the tradespeople to execute the ideas without compromising them – not upholding an arbitrary standard of precision. In every work there is an intrinsic idea about the workmanship required to foster the idea’s potential. Any discussion of craft without discussing the idea it serves is meaningless. Secondly, the nature of qualifying a “good” idea is uncertain ground. This is part of the designer/maker’s responsibility to pursue the ideas that continue to exhibit potential. The ability to determine which ideas have potential and those that do not are part of the domain of knowledge advocated for in this essay.

6 Steinberg, Leo. 1972. “Jasper Johns: The First Seven Years of his Art.” In Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art, by Leo Steinberg, 17-54. London: Oxford University Press.

Cause and effect.- “Explanation” is what we call it, but it is “description” that distinguishes us from older stages of knowledge and science. Our descriptions are better–we do not explain any more than our predecessors. We have uncovered a manifold one-after-another where the naïve man and inquirer of older cultures saw only two separate things. “Cause” and” “effect” is what one says; but we have merely perfected the image of becoming without reaching beyond the image or behind it. In every case the series of “causes” confronts us much more completely, and we infer: first, this and that has to precede in order that this or that may then follow–but this does not involve any comprehension. In every chemical process, for example, quality appears as a “miracle,” as ever; also, every locomotion; nobody has “explained” a push. But how could we possibly explain anything? We operate only with things that do not exist: lines, planes, bodies, atoms, divisible time spans; divisible spaces. How should explanations be at all possible when we first turn everything into an image, our image!

It will do to consider science as an attempt to humanize things as faithfully as possible; as we describe things and their one-after-another, we learn how to describe ourselves more and more precisely. Cause and effect: such a duality probably never exists; in truth we are confronted by a continuum out of which we isolate a couple of pieces, just as we perceive motion only as isolated points and then infer it without ever actually seeing it. The suddenness with which many effects stand out misleads us; actually, it is sudden only for us. In this moment of suddenness there is an infinite number of processes that elude us. An intellect that could see cause and effect as a continuum and a flux and not, as we do, in terms of an arbitrary division and dismemberment, would repudiate the concept of cause and effect and deny all conditionality.7

7 Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1974. The Gay Science. Vintage Books Edition. Edited by Walter Kaufmann. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York, NY: Random House, Inc.

The inferences from effects (work) are limited, and their linguistic articulation is automatically an anthropomorphized interpretation and offers little genuinely new knowledge about the world; only, perhaps a more nuanced description of a world and context that pre-existed the effect.

Critical determination (judgment) of the work thus also exists completely independently of the work. Works where a specific critical interpretation becomes canonically linked as the authoritative account are often the works where the artist has offered a specifically-communicated message or intention, which is essentially outlining the terms for critique. But if the terms of critique come from the designer, then a third-party arbiter loses his/her authority by deferring to the artists’ own parameters. The supposedly objective critic who speaks on behalf of society’s constructed value system is not even considered valuable – for who can claim objectivity; and who could rightly claim to have internalized the entirety of their society’s values? The only sensible option is to identify that only the artist/designer could offer the work its principal judgment of quality. Consider Donald Judd’s quasi-tautological statement about a work’s quality:

To begin again at the beginning in a proper philosophical manner, one person is a unity, and some how, after the long complex process, a work of art is a similar unity. But the person is fairly unintelligible and the art is intelligible. Primarily what is intelligible is the nature of the artist, either of the past or now. The interests, thought and quality of the artist make the final total quality of the work.8

8 Judd, Donald. 2016. “Art and Architecture (1983).” In Donald Judd Writings, by Donald Judd, 338-351. New York: Judd Foundation.

If we regard the artist/designer/creator as having a rigorous character and integrity, he/she has already deemed the result to be sufficiently commensurate with his/her intentions by putting it into the world. Critical hindsight or negative future assessments would not proffer a more authoritative account or judgment of the piece in question; but rather simply offer an alternative interpretation made available to the arbiter by changing ideologies and new information; or it proclaims a discrediting indictment of the artist for a faulty or misguided principal determination. But the body of work lives on, even with a loss of authority of the person(s) to which the work is attached. Not every building by Louis Kahn or Le Corbusier is a masterpiece. It is through the breadth of their body of work and aggregate of interpretations about the extraordinary examples that they survive the indictments on their bad projects. The bad projects though, are bad because they cannot inspire renewed interpretation about their functional, aesthetic, and social relations. But every so often a critic or user comes along and re-examines the previously admonished work and finds new meaning. In this way, everything is infinitely interpretable - and perhaps this is all they are.

The tenor and value of interpretation differs greatly depending on the role of the interpreter. The hermeneutic mode of interpretation9 as elucidated by the critic is different than the generative process that relies on interpreting a context or event as an impetus for new work. At a base level, new work is driven by the demand of an external source (person or criteria) and/or the compulsion to create on the part of the designer/artist/architect/maker. The capital structure that holds sway over the creative agent might determine the categorical discipline of the created work, but the human drive to create is the fundamental value. The drive to create is a provisional answer to the question of what motivates any human endeavor. Irrespective of a comprehensive ontology for existence, this paper is based on a belief that each of us are our own project. I am my project for my life – understanding and bettering myself in relation to others. But that project is not able to be tackled directly, but rather through mediating methods, namely forms of communication. The ways we work towards that larger project is to search for the right form of incremental projects - through creation. Philosophers find this form through writing; artists make art, politicians devise policies and orations, etc. But the people whose activities and occupations are in service of other people (admirable) or in service of capital structures (less admirable) at the expense of creative endeavor must find their release of creative energies through other means – often a biological/evolutionary response to procreate. Understanding that creative impulses drive our existence places additional value on the gestures of the agent. Regarding the interpretive mode of that agent/creator, it is impossible to presume comprehensive knowledge about the creative project in question without first being open to its own potential to change you, the creator. Interpreting and re-contextualizing the information available to you at that particular moment holds paramount value – perhaps more than deductive reasoning or exhaustive critical analysis. Intuition is the ability to decide in an instant, almost pre-cognitively, whether the interpretation of some context (an idea) is worth pursuing. It is a feeling that guides us towards producing work that attributes itself to an internalized value system.

Understanding the goal as a specific kind of relationship (aesthetic ideal) is the metric by which one’s intuition needs to operate. One motivation of this inquiry extends from an annoyance at the manner in which poetic or atmospheric works are discussed. A common trope is to evaluate the work as such “if it moves me.” But the question of how, why and to what degree it moves you is never entertained. Intuition guides the process towards the goal of specific kinds of movement characterized by how the relationship prompts you to deviate from the datum of openness and neutrality. In this instance it is not simply a matter of moving a person to feel more or to think more because it posits an ongoing relationship that accommodates both responses. The literary theorist Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht offers some insight about the kind of movement that addresses the sort of durational co-presence that is required for aesthetic experience to be affecting:

9 Language does me a disservice here. “The hermeneutic mode of interpretation” certainly seems redundant, but it is specified here as a counterpoint to a non-hermeneutic mode, in which we deal directly with the presence of a thing. “Dealing with the presence” of a thing could be the “non-hermeneutic mode of interpretation,” even though a linguistic interpretation is not being offered. Still, perhaps non-hermeneutic confrontation is a better way to delineate the two, and thus resolve the redundancy.

Finally, there are three aspects that give the epiphany-component within aesthetic experience the status of an event. In the first place (and I have already mentioned this condition earlier on), we never know whether or when such an epiphany will occur. Secondly, if it occurs we do not know what form it will take and how intense it will be: there are no two bolts of lightning, indeed, that have the same form and no two orchestra performances that will interpret the same score in exactly the same way. Finally (and above all), epiphany within aesthetic experience is an event because it undoes itself while it emerges. This is obvious up to the point of being banal, for lightning or for music, but I think it also holds true for our reading of literature and even for our reactions to a painting. No single meaning structure and no single impression of a rhythm pattern, for example, is ever present for more than a moment in the actual reading or listening process; and I think that, similarly, the temporality under which a painting can really “hit” us, the temporality in which we feel, for example that it comes toward us, will always be the temporality of a moment.10

10 (Gumbrecht 2004, p. 113)

SYSTEMS OF LOGIC

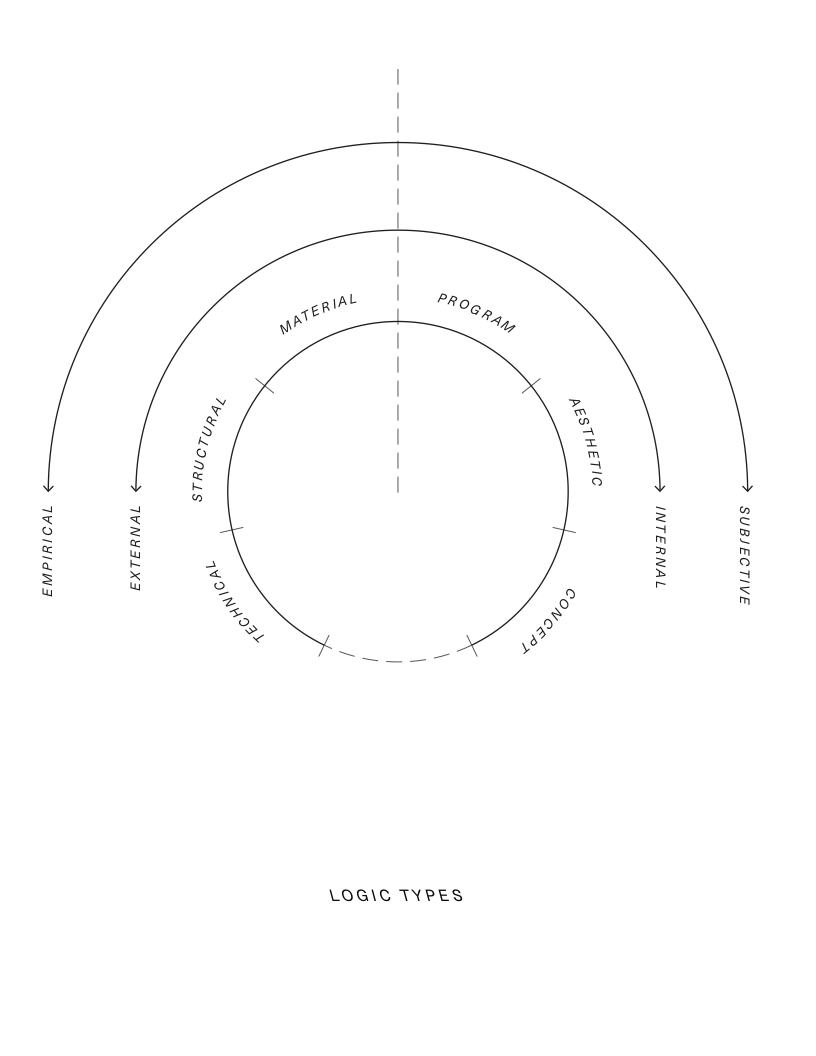

In a text about the work of a colleague, I wrote, “Objects have empirical concerns and subjective relations.”11 This asserts that an object acts as its own subject, and in doing so it relates to other objects with the particularity of their co-present sensible qualities and postures. This also acknowledges the more prosaic observation that an objects’ relations to other things are assigned hierarchy through a subjective (the viewer/observer) lens. Empirical concerns are the forces that govern our (physical) world such as gravity, tension/compression, friction, optics, etc. as observed & understood through human faculties. Through this duality of empirical and subjective considerations one might diagram the types of logic that inform decisions throughout a creative process as belonging closer to one side of the spectrum or the other. A neutral/centrist reading of such a diagram reveals that only the best (most interpretable) work responds to all systems successfully, but the project finds the particularity of its presence through the intentional subduing of the polar logic systems in favor of those closer to the center.

[Fig 1]

In generating a project there is a question of overlaps in these types of logic and – upon conflict of one or another system – the question arises about which logic supercedes another. The work described here assumes that all six types of logic are adhered to, though posits that the systems of logic closer to the middle are the ones meant to be indexed by its perceptible (built) reality. A provisional definition of each kind of logic might be required to understand its analogous expressions. Technical logic is, strictly speaking, the problem solving of a product’s function in relation to its physical/mechanical reality. For instance, a screw or a fastener may be required to secure one building element to another. This screw performs its function which is, relatively speaking, beyond the designer’s discretion. The designer has no control over the work it does because the work needs to be done. Structural logic is close to technical logic but finds its expression in relation to any number of human-driven variables such as occupancy loads, not to mention the relation of the structural system to a parti that has been developed with respect to other material, programmatic, aesthetic, or conceptual concerns. Principally, structural logic is a direct response to gravity, seismic, wind, and other forces imposed upon the thing by its environment. Material logic is dictated by the particular physical properties of a material and how it performs in relation to a task or proclivity as defined by the designer. This type of logic is still bound by an external object’s native characteristics, but finds some malleability based on the designer’s intentions. Programmatic logic is the system that defines how the spaces function in relation to the user’s goals as interpreted by the designer. At first glance this seems like objective problem solving, but this is based on a mountain of cultural and historical context that determines how the people in a given culture define their ways of living and using space. Aesthetic logic is similarly based on a cultural context but actually comes from an internal source where decisions are made with respect to the physical consequences. An obvious example is the superficial adjustment of a tile pattern to ensure the alignment of one piece to an external constraint such as a base board. Related to this is the use of reveals within a field of materials that expand and contrast at the same rate. There is a constructible sensibility that argues in favor of some of these decisions, but the inability to accept the consequences of the steps that led to such a decision is a concession towards an aesthetic turn. Conceptual logic, by contrast, is the logic of an idea. This approach is favored in academia wherein an idea (concept) sets up the arbitrary parameters against which each successive decision must measure itself. Often the idea is one of pure bias: an intuitive reaction or singular vision for the project. The genius sketch on a napkin is the romantic version of these events. Surely this is the most difficult system to codify, but if this subjective outer edge of the spectrum can reveal a route towards the middle, then it is in approximating its polar counterpart. An idea related explicitly to empirical concerns, as opposed to unabashed proclivities, may be the most acceptable basis for a concept. Similarly, the empirical issues which relate most directly to the conceptual logic may be the most appropriate to find expression in the final product.

Previous theories of art and architecture created a hierarchy among these logics and – in the theory’s dogmatism – argued for one logic to make itself most manifest in the finished work. Consider the Hi-Tech architecture of Norman Foster, Renzo Piano, and Richard Rogers as embodying the leftmost ideal. Hermann Hertzberger, O.M. Ungers, and the architects under the Structuralist, Rationalist or Neo-Rationalist umbrella might find a home in the region that advocates for the structural logic of a building to be most manifest. Material and Programmatic logics are perhaps the most difficult to articulate because the vast majority of the work today falls into one of these categories. Louis Kahn may be the perfect embodiment of the two, through his development of Servant and Served spaces as registrations of programmatic distinctions; and his quietist, animist approach to materials and their ambitions. In the material logic realm, one might find Carlo Scarpa, whose palette of materials and use of material motifs provided his projects with the most coherent narrative of the various idiosyncratic moments within his work. Sigurd Lewerentz is another example where the material logic overwhelms the others – the constraint of not cutting a brick at his church in Klippan is a well-documented narrative of the project that relays a subjective concern for a material to retain its original presence without submitting it to errant craft or needless waste. More heavily on the programmatic logic is OMA, whose building program analysis diagram-cum-building form approach has radically shifted the way architecture is presented to clients and the public. This strategy employs the power of visual reasoning wherein the two-dimensional graphic arrangement of program square footages on a screen translates into a three-dimensional formal rationalization for the most radical decisions related to the building’s shape and posture. Aesthetic logic is also a logic rooted in the ethical virtues of the day - most of the decorative forms such as Baroque, Renaissance, and Classical styles are most responsive to an aesthetic logic, albeit serving a religious ideal. Today this can be seen in the type of work that purports to serve a rationalist or structuralist agenda as a value, but - in fact - relies on superficial alignments and ploys to make the argument. As for the architects who favor a conceptual logic above all others, consider Peter Eisenman’s pursuit of syntactical and literary meaning as defined by overlays of grids, with a rigor that seemingly disregards the importance of its physical existence in relation to human habitation. Not included in this group are those practices who participate almost entirely in speculative, hypothetical, or utopian projects such as DOGMA (Pier Vittorio Aureli) or Lebbeus Woods. In any given work of architecture, every material thing or circumstance asserts its own (positive) presence. The presence of each material thing and circumstance submits itself to the question of which system of logic governed its insertion into the project. Perhaps atmosphere is what is left over in a project when the positively present components of a building adhere to all six systems of logic fundamentally, but only the central four are indexed by its present circumstances.

The causal relation of an idea to its consequent manifestation is not always relevant because it denies the fluidity of a process where ideas must adapt to be made possible. The subjectivity of the idea is too internal to require that it find resonance in the product’s external relations. Because the product is endlessly interpretable and finds meaning in innumerable expressions, the exactitude of the idea’s index does not need to translate from the source. The autonomous presence of the work is at odds with the subjective bias of the designer/maker when the work is complete. The particularity or specificity of the idea is embedded in the product, but the explicit call to its idea inhibits the user/critic to determine its relevance on their own accord. If it is the work of the critic to drain a piece of its meaning or value, then the architect, in making the idea so patently unambiguous – either through overt built expression OR through verbal articulation of the idea – has already drained the work of this meaning by the time it is constructed. The technical logic by contrast is always there. Without it, the building would not work. But the additional layer of information reminding the users of a component’s mechanics as they relate to empirical parameters can paradoxically serve to disconnect the user from relating to the presence of the thing on the terms it sets out for itself within the empirical world. The plaintive bleating of an expressed lintel can be a pathetic call to attention at the work it is seemingly doing. The lintel’s expression is an overt defiance of gravity in service of a value system that purports to be about honesty and transparency of its function, but which is actually only an expression of the idea of honesty – for the steel reinforcement within a concrete lintel is responsible for most of the work, and yet does not find expression. But as with each system of logic, the particular strategy or designed element – in this case, the expressed lintel – is not so much the problem as the value system that justifies its expression. A quietist approach accepts things as they are so that they may be what they need to be. One need not conceal the lintel, but it will always fail to serve an ideology without some other inherent conflict, which is not necessarily a problem if the ideology can accommodate conflict and contradiction; which honesty of construction does not.

11 2018. “Vertical Textile Shape (VTS) Horizontal Textile Shape (HTS) | Jonathan Muecke.” Kvadrat. https://kvadrat.dk/my-canvas/ vertical-textile-shape-vts-horizontal-textile-shape-hts- jonathan-muecke?

NEUTRAL MODALITIES

Rather than further the agenda of a particular set of values or ideologies, a centrist mode characterized by finding manifestations of the central systems of logic defined above aim to find idealized relations of the people and the objects and spaces with which they interact in service of our mutual co-presence. While the subject/object dichotomy has been discussed ad nauseam and has led many artists and architects down a path which privileges individual experience above everything else, the central hypothesis of this essay relies on a fundamental redistribution of terms within this dichotomy. Equilibrium of reception is a very fine degree of cognitive oscillation between subject and object. Tension – or apparent contradiction, as others might call it – is a wider degree of oscillation in the relationship. But both equilibrium and tension represent a concentric stability – an active deviation and subsequent counteraction. Not coincidentally, these concentric responses also characterize the two most commonly accepted aesthetic ideals: beauty (equilibrium/harmony) and the sublime (tension/contradiction). The cognitive oscillation that informs these relations is a fluctuation between thinking and feeling if one is to buy into this duality. For Donald Judd, this is a natural worldview:

Rather than further the agenda of a particular set of values or ideologies, a centrist mode characterized by finding manifestations of the central systems of logic defined above aim to find idealized relations of the people and the objects and spaces with which they interact in service of our mutual co-presence. While the subject/object dichotomy has been discussed ad nauseam and has led many artists and architects down a path which privileges individual experience above everything else, the central hypothesis of this essay relies on a fundamental redistribution of terms within this dichotomy. Equilibrium of reception is a very fine degree of cognitive oscillation between subject and object. Tension – or apparent contradiction, as others might call it – is a wider degree of oscillation in the relationship. But both equilibrium and tension represent a concentric stability – an active deviation and subsequent counteraction. Not coincidentally, these concentric responses also characterize the two most commonly accepted aesthetic ideals: beauty (equilibrium/harmony) and the sublime (tension/contradiction). The cognitive oscillation that informs these relations is a fluctuation between thinking and feeling if one is to buy into this duality. For Donald Judd, this is a natural worldview:

If the nature of art is the same as our nature and if there is no division between thought and feeling, art is cognitive just as our experience is. And art is no more inferior than is our experience as a whole. [...] I’ve always disliked the division between form and content and have never known what to answer when asked “but what is the content?,” “what does it mean?” Recently it occurred to me that this unreal and uninformative division is just part of the larger division between thought and feeling. The division between form and content neither agrees with the very reciprocal process of developing art nor the viewer’s experience in looking. It also has the same absurdities as the division between thought and feeling. Both halves are meaningless and without any function when considered alone. There is no form that can be form without meaning, quality, and feeling. We even have a feeling about a rock, about anything. It’s a contradiction to make a form that is meaningless. It’s also impossible to express a feeling without a form. It couldn’t be said or seen. Embodiment is the central effort in art, the way it gets made, very much something out of nothing. Everything happens together and exists together and does not divide because of a meaningless dichotomy.12

12 (Judd, Art and Architecture 2016)

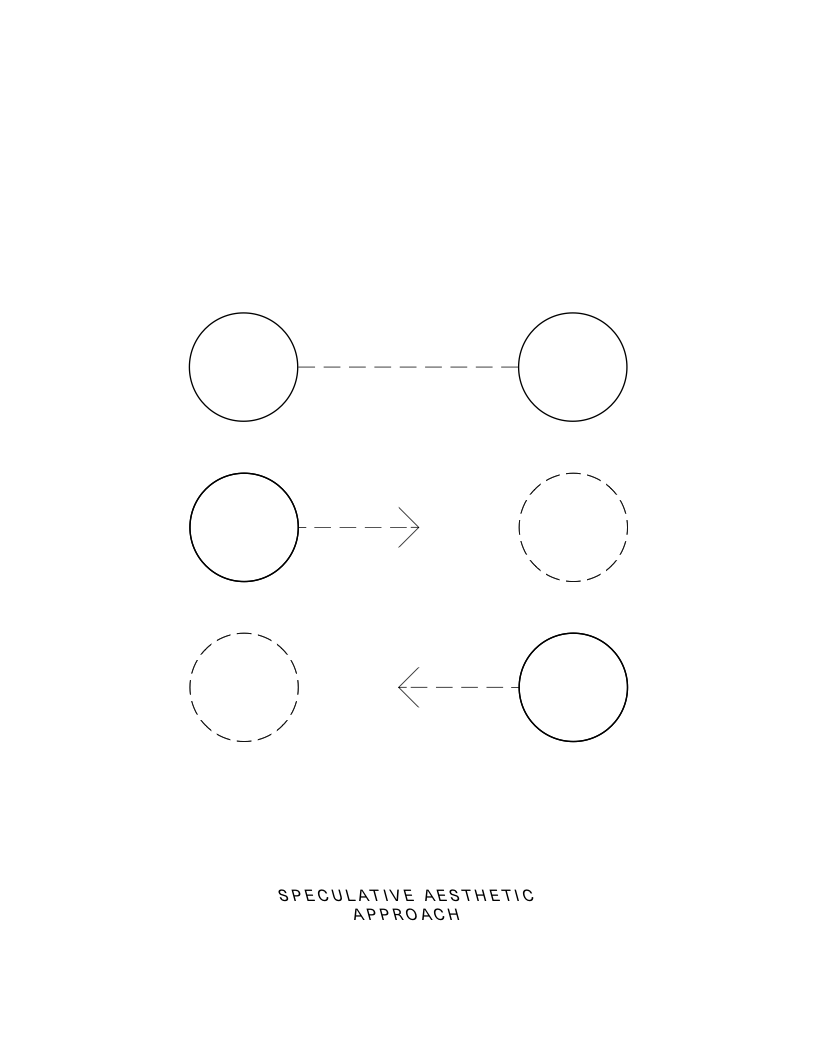

Both halves are meaningless without the other. Thinking – or the processes and words we most associate with a cognitive direction towards it, such as reasoning, speculation, logic, etc – is merely a provisional term that lives on the same circular spectrum as feeling, or the processes and adjectives we might associate most directly with feeling, such as doubt or intuition.13 Thinking is often linked with what is known or can be known about the object in question, whereas feeling is generally commensurate with what is not known about an object or event. We feel things about objects often before we think about them; and the feelings often inform the thinking, and vice versa.

13 Consider that feeling may be different from

emotion. Perhaps happiness and sadness are

emotions – involuntary responses that are the

product of the thinking and feeling that we do to negotiate our actions/reactions with the

world. Emotions penetrate more deeply into

the autonomy of our being than thinking or

feeling do. Emotions may be deeply embedded

in our unconscious mediation with the world,

whereas thinking and feeling probably operate

closer to the surface at, or just below the

conscious realm. In considering a work of art

or architecture that moves the viewer it is

probably meant that the work elicits emotions.

Emotions, I think, are internal and can be

expressed through thinking and feeling and

physical markers. However, because of this

internality, I have not included emotions in the

aesthetic relationship described below.

[Fig. 2]

[Fig. 3]

Within discussion of aesthetic responses, it is generally understood that the “sublime” refers to an experience that one undergoes at the apprehension of a thing or an event. It is the world outside acting upon you, the subject, that prompts the undergoing of the sublime. Despite this directional relation, “beauty” - the other most frequently cited aesthetic ideal - still generally refers discretely to an object or event that has whatever qualities are associated with beauty in that particular cultural milieu and epoch. An alternative to this view is to redistribute these terms to refer to the relational interplay of the subject and object as opposed to an experience afforded by the object to the subject or the determinant judgments afforded by subject onto the object. The conviction that the sublime and beauty are possible only through a durational co-presence of subject and object as distinct from the confrontation with the illusionistic representations of a unique aesthetic contribution, which prompts merely the thought of beauty or sublimity, delimits the objects and contexts that can cultivate these aesthetic relations from those that cannot. In other words, the aesthetic ideals of sublime and beauty are only possible when dealing directly with the work in question – neither memories nor representations of the works can elicit these responses for the referent is too directly associated with the work. A project not yet built contains the potential of its reality. A built project that elicits a sublime or beautiful relationship contains the potential of indefinite interpretation – it is potent. For works no longer extant – such as Michael Heizer’s Munich Depression, or Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s American Folk Art Museum, the relation changes from the original project because of its new reality. A demolished or temporary project no longer has potential or potency because the identity of its form has morphed into an entirely new form (documentary representation) or a non-form (memory). Just as a deceased loved one cannot provide an active relationship with you, the memories of the person and your relationship spark feelings and thoughts about the relationship. The terms of the relationship have changed because the presence of the objects have exhausted their potential energies in becoming something new or through a draining of their meanings.

[Fig. 4]

[Fig. 5]

[Fig. 6]

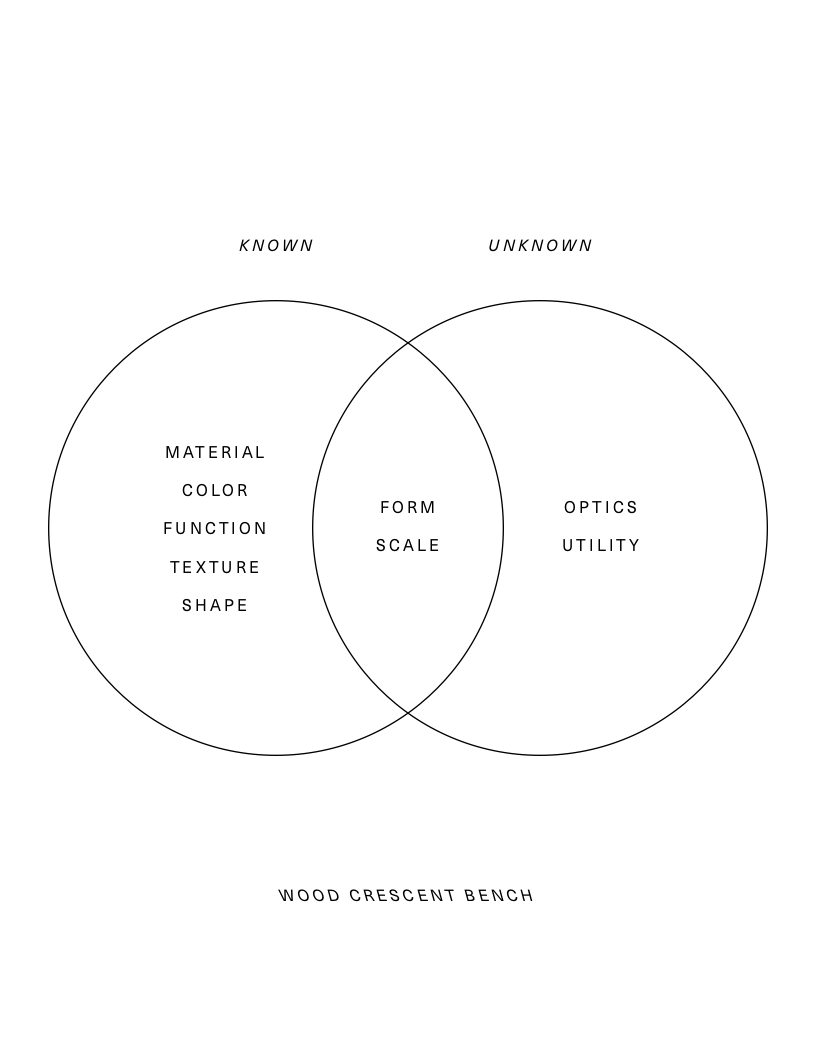

[Fig. 6]The object that elicits renewed interpretations does so through its potency – that is its capacity to call into question the outer systems of logic (technical, conceptual) and thus provide the relationship with new frames of reference beyond the purely subjective or empirical parameters which typically govern day-to-day existence. From the Latin root potentia, denoting power, potency shares its origin with a more commonly used term: potential. One may understand potential broadly as the latent possibility for an event to occur. A potent object or space would be one that establishes a strong enough link for the aesthetic relationship to occur – and for the subject to want to sustain it. It is a level of interest that would colloquially be called captivation. In a captivated state, one experiences a state of immersion in an environment or a unity that is a simultaneity of thoughts, feelings, known qualities, and unknown qualities. In short, making room for the unknown is a way to preserve and perpetuate the potential of a thing-in-progress, a truer metaphor for the human project. The artist and thinker Lucy Cotter offers her account of research into forms of non-knowledge and their value in a process of artistic production:

This is what makes art so exciting and unique as a site of ‘knowledge production,’ yet it is also why artists find the term ‘knowledge production’ so misplaced. Building on the work of Sarat Maharaj, I have introduced the notion of ‘non-knowledge’ in several dialogues to better describe this open-ended form of knowledge, which remains in flux as a subjective embodied viewing experience. Non-knowledge lies in “forms of knowledge that are often below the radar of our conscious thought and which can bypass our rational minds to incorporate contradiction and intuition.” It is constituted not only by what is not yet known, but also includes what is unknowable, or what cannot be assimilated as (formal) knowledge. This is where artistic research becomes antagonistic to academic knowledge as such. Artists work with areas that are not only beyond current thinking on certain subjects and situations, but also off the radar, moving into unknowable territory. They embrace this unknowability, being comfortable with holding open spaces of not knowing that confound traditional research. Artistic research thus revolves around articulating new questions without seeking answers.14

14 Cotter, Lucy. 2017. “Reclaiming Artist Research - First Thoughts...” Edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/mjfar.30. MaHKUscript: Journal of Fine Art Research 2 (1): 1-6.

As the creative agent/actor one must assimilate into a process that can find production and creative resolution while confronting this epistemological barrier of non-knowledge, contradiction, and intuition. Naïve intentions – and our awareness of them – constitute a strategy that bypasses the need to know a process. Appropriation is another strategy that enables one to borrow at will from the world of creative production towards a resolution that separates the authority of the agent from the work. An account of trickster mythology approximates how to operate at this limit of knowledge with grand visions of upheaval. Lewis Hyde positions tricksters at the periphery of the systems they aim to subvert; but their aim is always directed towards the central core of the system. “Trickster the culture hero is always present; his seemingly asocial actions continue to keep our world lively and give it the flexibility to endure [...] If trickster stirs to life on the open road, if he embodies ambiguity, if he ‘steals fire’ to invent new technologies, if he plays with all boundaries both inner and outer, and so on – then he must still be among us, for none of these has disappeared from the world.”15 The trickster knows how to use coincidence and accident to his advantage – an amoral world view enables him to be “creator and destroyer, giver and negator.”16 Without a specific strategy in mind, one must believe that they have cultivated a thorough body of métis or tacit knowledge to negotiate the terms of this epistemology. Primarily linked to biological/evolutionary traits linked with hunting, trapping, and guarding against danger, métis is a method of working through the uncertain parameters of one’s environment to further one’s own agenda.

15 Hyde, Lewis. 1998. Trickster Makes This World. New York: Straus and Giroux, p. 9.

16 Ibid. p.10

There is no doubt that métis is a type of intelligence and of thought, a way of knowing; it implies a complex but very coherent body of mental attitudes and intellectual behavior which combine flair, wisdom, forethought, subtlety of mind, deception, resourcefulness, vigilance, opportunism, various skills, and experience acquired over the years. It is applied to situations that are transient, shifting, disconcerting and ambiguous.17

17

Detienne, Marcel and Jean-Pierre Vernant. 1991. Cunning Intelligence

in Greek Culture and Society. Translated by Janet Lloyd.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Having cultivated métis, one can intuit and feel his/her way through situations which seem too difficult to resolve or uncertain in their consequences. It is a way to know the way through doing it, rather than preconceiving it. For Michael Polanyi, tacit knowledge functions similarly – but is also a kind of knowledge that is beyond words. “We can know more than we can tell,”18 says Polanyi. However, Polanyi also recognizes that this type of knowledge is not a tool towards a project of acquiring a comprehensive critical understanding of the universe. Bringing us back towards forms of knowledge beyond conscious understanding, he tells us, “We can see now how an unbridled lucidity can destroy our understanding of complex matters. Scrutinize closely the particulars of a comprehensive entity and their meaning is effaced, our conception of the entity is destroyed.”19 An awareness of our acting is perhaps all that is needed to work in this realm, but it is also with an understanding that the desirable outcome of the work operates as an artifact of this in-between-ness that expresses its ambiguous origins and potential outcomes.

18 Polanyi, Michael. 1966. The Tacit Dimension. New York: Doubleday & Company. p. 18

19 Ibid.

SENSIBLE ARCHITECTURE

The ontology championed here can be translated into design as an architecture that represents and fosters stillness. What is clear to me among the practitioners of this kind of work is that there are perhaps more differences among them than there are similarities, but they find common ground in a formal commitment to stillness, a measured politic that refuses categorical overextension or hypercritical analyses that would sway the scales towards dogma, a synthesized understanding of historical reference, and a profound optimism for the future without clamoring for its arrival today. The practitioners and their works appear varied, some favoring extremely digital methodology, while others speak of the importance of making, craft, and tradition; but an absolutely essential criteria for these practitioners is a belief in the value of the unknown in addition to what we can know. Impossible to describe in corporeal terms, the unknown can reveal itself in a process as an intentional naïveté, in a built project as a profoundly mysterious interplay of light and shadow, as unintentional consequences and chance encounters that emerged from an attitude that did not require the exhaustive articulation and decisive expression of each moment within the creative project. Philip Ursprung and Jürgen Mayer H refer to this kind of work as beige, a distinct departure from modernist “white” orthodoxy. “Beige is not radical and purist like white; it is moderating and popular. Beige allows formal nuances, the play with materials, subtle response to the spatial, and historical context [...] It does not join in the lament of the homogenization of architecture, but quite optimistically outlines its potential.”20 Christopher Hawthorne wryly (and fondly) refers to examples of it as “boring” architecture.

The ontology championed here can be translated into design as an architecture that represents and fosters stillness. What is clear to me among the practitioners of this kind of work is that there are perhaps more differences among them than there are similarities, but they find common ground in a formal commitment to stillness, a measured politic that refuses categorical overextension or hypercritical analyses that would sway the scales towards dogma, a synthesized understanding of historical reference, and a profound optimism for the future without clamoring for its arrival today. The practitioners and their works appear varied, some favoring extremely digital methodology, while others speak of the importance of making, craft, and tradition; but an absolutely essential criteria for these practitioners is a belief in the value of the unknown in addition to what we can know. Impossible to describe in corporeal terms, the unknown can reveal itself in a process as an intentional naïveté, in a built project as a profoundly mysterious interplay of light and shadow, as unintentional consequences and chance encounters that emerged from an attitude that did not require the exhaustive articulation and decisive expression of each moment within the creative project. Philip Ursprung and Jürgen Mayer H refer to this kind of work as beige, a distinct departure from modernist “white” orthodoxy. “Beige is not radical and purist like white; it is moderating and popular. Beige allows formal nuances, the play with materials, subtle response to the spatial, and historical context [...] It does not join in the lament of the homogenization of architecture, but quite optimistically outlines its potential.”20 Christopher Hawthorne wryly (and fondly) refers to examples of it as “boring” architecture.

20 J. MAYER H. und Partner, Architekten and Philip Ursprung. 2017. “Cosmic Latte.” In MAKE NEW HISTORY: 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial, edited by Mark Lee, Sarah Hearne, and Letizia Carzoli Sharon Johnston. Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers.

A boring building in 2017 is a building with something meaningful to say. To think of it merely as a pendulum swinging back toward a more balanced architecture is to underestimate it. It is also a wrecking ball (another solid and monochromatic form, a basic shape, an archetype) taking down a sensibility, a kind of machismo and self-satisfaction, that desperately needed razing — one that was taking up too much space and blocking too much sunlight, that was giving other kinds of architecture very little chance to grow.21

21

Hawthorne, Christopher. 2017. “Boring Architecture? Yes, Please.”

Los Angeles Times. November 16. Accessed November

2017. http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-ca-cm-

building-type-boring-buildings-20171119-htmlstory.html.

These accounts are close to the aim of this essay, but they each use language that does more disservice to the works than perhaps the authors realize. The subtlety of the work is its inherent interest. Determining what the work says and feeling its presence despite the apparent economical beige-ness or ostensibly boring forms gives it its vitality. To praise its boring-ness or to glorify some banal attribute as a constitution of its inherent value is ludicrous. That which is boring or banal is, by definition, inferior to something of interest. This middle ground for which I desperately yearn in this hysterical political age could simply be called sensible. And upon the sensible ground which it treads, it has the flexibility and the range to offer both rhetorical solutions and projections, as well as positions that do not find themselves so eager to out-do the previous version in the name of progress or innovation, but rather offers a new lens on familiar patterns. This neutral zone is not ambivalent though: the middle is the broadest domain, and thus offers the most flexibility for how to work and how to adapt. A car in neutral is ready to act – it contains the full potential of its action. The middle offers a buoyancy that enables one to posit directions and effects that veer towards some end or another in the service of human enterprise but does not rely on polemic or categorical statements in service of some singular agenda. Geopolitically, this neutrality is no better exemplified by Switzerland; that small country centered between Italy, France, Austria, and Germany that has produced some of the most influential architects and designers we have ever known, notably Le Corbusier, Peter Zumthor, and Herzog & de Meuron. The single most remarkable aspect of each of these three practices is the breadth of their work. Although Le Corbusier earned renown for two distinct phases in his career, which can be characterized as the development of a sensibility which refuted his earlier modernist orthodoxy, his body of work cannot be selective about what it includes. It is all of it – and it is in its variety that it holds value. And while Zumthor and H&dM have tendencies that characterize their work, taken as a whole, their works are notoriously difficult to pin down in stylistic terms. Though they continue active practices, and their works continue to inspire renewed interpretations and dialogues, their place in the canon of shapers of the built environment is secure. Among current practitioners there is a younger group of disparate architects around the world who – in the aggregate of the work they each produce – embody this neutral sensibility. The fashionable term used to describe a group of practices that are objectively unaffiliated with one another and do not necessarily identify with the approaches of the others, is to call them a constellation – where each individual practice is its own star, asserting its own relevance and significance irrespective of the others, but when grouped together forms a picture that reflects what it means to be doing work in this particular day and age. First though, it is important to set up an expectation for how to understand this grouping.

In her 1965 essay ABC Art, art historian Barbara Rose shifted the way she spoke about a group of contemporaneous artists that would later come to be associated with the Minimalism movement. Seeking not to define the ideologies and tendencies exhibited by these artists under the umbrella of a particular style, she instead spoke of shared sensibilities among this disparate group. Up until that point, style could reference a number of objectively analyzable traits among a series of works that were produced in relative simultaneity. This enabled art historians to develop historical categories such as impressionism, post-impressionism, surrealism, Dadaism, abstract expressionism, etc. The artists that were doing essentially minimal work though, seemed to have vastly different approaches that resisted this kind of categorization. The work of Donald Judd for instance relied on a machined aesthetic that was very different from the works produced by Frank Stella at that time which – although minimal in its color, form, composition, and materials – still indexed the imperfect motion of his hand at work. Rose outlines her strategy and remarks on some observations about the artists’ tendencies,

So, for the present, I prefer to confine myself mostly to describing the new sensibility rather than attempting to interpret an art that, by the terms of its own definition, resists interpretation. However, that there is a collective new sensibility among the young by now is self-evident. Looking around for examples, I was struck by the number of coincidences I discovered. For example, I found five painters who quite independently arrived at the identical composition of a large white or light-colored rectangle in a colored border [...] though again, it was nearly impossible to pin down a specific image or sensation, except for the reaction that they weren’t quite what they seemed to be. In the same way, three of the sculptors I’m considering (Carl Andre, Robert Morris and Dan Flavin) have all used standard units interchangeably [...] but still, another element has insinuated itself, preventing any real equations with constructivist sculpture.

It is hard to make more specific remarks without incurring Boss Tweed’s criticism.22 So rather than guess at intentions or look for meanings I prefer to try to surround the new sensibility, not to pinpoint it.23

22 Earlier in her essay, she remarks upon the bewildering experience of a spectator who is caught up in his/her own subjectivity: “Such subjectivity would of course be rejected by the artists in question with the notion of Boss Tweed: ‘Balderdash is twaddle at any speed.’”

23 Rose, Barbara. 1965. “ABC ART.” Art in America, October-November, p. 62.

The subsequent art movements such as post-minimalism, conceptual art, body art, appropriation art, and so forth exhibit a pluralism of sensibilities as opposed to a series of discrete styles, which has inhibited the effort of categorical distinction among these groups of artists. A point of contention, however, which elicits a resistance among the artists to be associated with whatever term they are labeled under, is that the expectation of the perceiver has not necessarily adjusted with the language of the critics and historians. It is still a human instinct to group and categorize things under a style for expediency, instead of accepting the indeterminacy that comes with understanding a general sensibility so that one may understand the particular, specific nuances of the artist or artwork being apprehended on its own terms, in relation to its specific context. The tacit reaction among listeners that some artist is a Minimalist artist is to nod in approval without necessarily considering the specifics of his/her practice relative to their context, as opposed to the biased understanding that comes with viewing his/her work through the lens of Minimalism. The instinct is to brush aside any thorough understanding in favor of a generalist acceptance into the educated elite that understands the meanings of these groupings. The listener feels part of the public of people equipped to discuss the work of art because he/she has a cursory understanding of the language to do so, but the dialogue gets further and further from the specificities of the work itself. The communicability of the work (and the ease with which it fits under a category) facilitates a broader audience to receive it but opens it up to a draining of its specific existence if we are to only regard its hermeneutic meaning to constitute its value. Still, Rose concludes her essay by alluding to an essential trait of the artists’ sensibility that belies the purported absence of content among their work. She says, “As Roger Shattuck says of Satie’s music, ‘the simplest pieces, some of the humoristic works and children’s pieces built out of a handful of notes and rhythms are the most enigmatic for this very reason: they have no beginning middle and end. They exist simultaneously.’ So with the multiple levels of an art not so simple as it looks.”24

Far from drawing a direct comparison to the “Minimalist” movement in art of the 1960’s, I only wish to set up the terms of a sensibility and to point to a few coincidences among a current trend in architectural work today. Today, a number of small offices continue to write about their work and their process with a similarly enigmatic sensibility as each other, and with eerily similar language as can be found throughout art history from the 1960’s onward. The constellation of practices do not form an obvious grouping or style, but rather hover around similar ideas of ambiguity, naïveté, intentionality, interpretation, and tacit knowledge as both driving forces in their process, and as effectual aspects of their finished work. Like the minimalists, they have been called boring, and ordinary – but have also been characterized here as embodying a somewhat neutral sensibility. If recent issues of the contemporary architectural journal San Rocco are any indication, some of these architects might reject any association with this group of minimal artists.25 But again, the reference is not to imply deliberate association or comparison, nor necessarily to offer a definitive account of what either group was doing, but simply to point out a similarity among sensibilities. Among this group of current architects, which was on full display at the 2017 Chicago Architectural Biennial, I think four practices in particular have found ways to exploit their process in the production of their work, which has some kind of intellectual or critical currency within today’s architectural discourse. Some of the practices remain steadfast in separating the work they do that is to be considered architecture, while others are more comfortable in a mixed terrain because their practice is devoted to a research that concerns both art and architecture.

The British practice 6a Architects produce work that is continually difficult to characterize because of their beliefs in idiosyncratic detail and gesture as responsive to coincidental interpretations of their context. As advocates for bricolage and self-proclaimed believers in métis, they rely on anthropological research and archival photographs to provide the generative impulse of many of their projects. The intentions inform a process, but the results reveal additional consistencies within their body of work that remain unspoken.

24 Ibid. p.69

25 The “Call for Papers” for San Rocco 9: Monks and Monkeys offered railing critique of minimalist art and architecture, which can be found here: http://www.sanrocco.info/ callforpaper/monks-and-monkeys

The “Call for Papers” for San Rocco 14: 66 is a nostalgic call to return to an idealized 1966, after the minimalist movement had its way, but before post modernism was reduced to a caricature of itself: http://www.sanrocco.info/ callforpaper/66-1

We are really interested in chance and accident. Not so much as a theoretical position within the work, but rather because that’s the way the world works. Our work is driven by an interest in how places transform, in how the world transforms. And if you are interested in the way that architecture engages in the world you simply have to accept accident. Accidents, opportunism, coincidence are fundamentally human values, they just happen.

[...]

The starting point is not to make a category of what is heritage and what is not. In other words, not to make a distinction between what has a value and what doesn’t. Those academic and legal categorizations package up history as a kind of commodity. What is much more interesting is to say: It’s all here. All of these fragments bear witness to the human lives lived in this bit of city, both the great moments of those lives and their tragedies. Basically our approach is not to judge. That’s what makes the architect slightly different to the historian and certainly different to the conservationist. The conservationist comes in and draws a table of relative merit: that’s very important, that’s slightly important, that’s not important. We find that frustrating. What you need to do is to engage with all of it and try to understand how it came about in order to decide how you are going to act on it in the future, for the future. One very important thing that the conservation and heritage people have forgotten about is that the history and the future only exist in the present. We don’t think it’s for us to judge when history has meaning and when it doesn’t.26

26 Kubisty, Julia. 2015. “Quiet Space Making: 6A Architects.” thisispaper. November 19. Accessed April 2018. https://thisispaper.com/ issue-2-6a-architects/.

In their Cowan Court project, the apparent banality of the form is undermined by subtle details that abstract empirical and subjective issues through the use of scale. Composed of three floors, each level is cantilevered slightly (by roughly the thickness of a wall) from the floor below. This scale of cantilever is not the heroic structural solution of modernity, but rather a subtle trick that recalls a simple technical solution of shedding water. Each floor is like a shingle overlapping the one beneath it. The window pattern initially appears mundane, but a module shift prompts the eye to move to the right, reinforcing the effect of the cantilevers until one arrives at the corners of the building. The corners, however, do not register this overlapping, prompting a second look. A look at the base of the first floor compared to the roofline on the third, it is apparent that each level curves slightly in the middle, recalling the optical refinements and entasis at the Parthenon and other Doric structures. The topmost band of reclaimed timber is infilled with pale oak boards cut in a lozenge shape, acting as an architrave for this pseudo-classical, timber brutalist structure. The material palette is limited – in order of predominance, the exterior view only registers its dark reclaimed oak cladding, new, pale oak windows, and concrete, with the spare use of galvanized metal. The project is coherent through its material presence, facilitating an understanding that it can be its own subject; not merely an object for looking at or a machine to provide a particular kind of experience. The scaling up of found details and vague references to a disciplinary history are repeated in their entry to the Vertical City for the 2017 Biennial wherein the millwork profiles within a room of their Raven Row project were collapsed into a single contour, revolved, and scaled up to form their rhetorical proposal for the new Chicago Tribune tower. The arbitrariness of intention in relation to its “design context” gives way to an understanding that this tower has its own presence of shape, form, material, and cultural context which defy its site-driven history.

[Fig. 7]

Fig. 7

Cowan Court Exterior

6a Architects

Photo: Johan Dehlin

2016 http://www.6a.co.uk/projects/ selected/cowan-court (accessed April 30, 2018)

[Fig. 8]

Fig. 8

Cowan Court Plan

Drawing by 6a Architects

2016

http://www.6a.co.uk/projects/ selected/cowan-court (accessed April 30, 2018)

Pezo Von Ellrichshausen in Chile condones intuitive, “non-intentional” procedures based on anonymous arbitrariness and systematic resolution. They consider their work to be contributions to an autonomous body of knowledge of architecture and rely on their geographic and disciplinary precarity as an alibi for their naïve intentions.

The intention alone is no other than a potential decision, a kind of movement without any inertia, already prefigured as a deliberate act.

[...]

Our open-ended assumption here is that it is perfectly reasonable to implement a set of arbitrary intentions during the development of an architectural project. This is not only a very common practice, which in fact occurs more often than is officially admitted, but a fundamentally redemptive and empowering driving force for the practice of architecture. In this somewhat emancipated way, the architect could replace his subjective role as author by that of an arbitrator, an equally subjective figure but one who keeps to a less pretentious corner.

[...]

As we have stated, there is no possible work of art without an intention. We profoundly believe that the final constitution of a building should be neither more nor less than a silent unit where the intentions of the architect and the intentions of others, even the interference of accidental forces, are simultaneously crystallized without any distinction. Even if the production of architecture without architectonic intentions seems possible, we go on practicing with the firm belief that it is impossible to produce a good work of architecture without a good reason and a real purpose.27

27 Pezo, Mauricio and Sofia von Ellrichshausen. 2017. Naïve Intention. New York: Actar Publishers.

Arguably their most renowned project, the Poli House is an example of a project where a set of arbitrarily-enforced rules determined the resolution of the parti. Perched on a clifftop in Coliumo, Chile, the project is idyllic in its photographic representation in relation to its extraordinary site, but the interior is where the project finds its value. A thickened perimeter belies the usual strategy to maximize glass when the views are especially desirable. Within the thickened perimeter one find the stairs through a raumplan-like section, as well as the service spaces such as showers, bathrooms, closets, and every typical back-of-house function. As one circulates around the perimeter, an atrium extends the full height of the house in the northwest part of the plan. On the north and west elevations, all the fenestrations are the same size: each window is the same size as the double doors that ventilate and provide access to the house. On the south and east sides, where the corresponding interiors are more compartmentalized, one finds windows principally of two sizes; the larger of them correspond to a cut through the thickened perimeter to habitable “rooms”, whereas the smaller operable windows open within the thick perimeter for the bathrooms, and stairs. The material palette is also limited and austere: vertically-oriented board-formed concrete exterior, and painted white wood boards on the interior non-structural walls, with the internal concrete walls painted white to match. The result is an immersive environment punctuated by quasi-room sized thresholds (not merely ‘openings’) that extend the interior outwards and the exterior inwards.

[Fig. 9]

Fig. 9

Poli House Plans

Drawing by Pezo Von Ellrichshausen

2005

https://arch.iit.edu/prize/mchap/ selected-works/project/poli-house (accessed April 30, 2018)

[Fig. 10]

Fig. 10

Poli House Interior

Pezo Von Ellrichshausen

Photo: Cristobal Palma

2005

https://arch.iit.edu/prize/mchap/ selected-works/project/poli-house (accessed April 30, 2018)

The Belgian practice OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen believes in a more intentional approach than PVE, but still favors an ambiguous reception of their projects. Relying on appropriation from a disciplinary history that includes classical references such as Bramante and Palladio, their work often aims to show the potential of re-contextualized historical references through contemporary formal resolutions. An economy of gestures is critical for this approach to land, however, for it is not simply recapitulation, but rather an aloof reprisal of old ideologies through contemporary, reductive strategies to mediate the inner and outer perception of the work; or rather to bridge the gap between the intention of the original ideas and the phenomena of the experienced space.

Good architecture is a good project. It seems unavoidable, in this contemplation of such a series of ponderous concepts, to end up with a tautology. But this is not a tautology. As a set of related concepts, both architecture and the project provide access to a domain in which intentions only indirectly become clear. The project must, as it were, be able to speak for itself. Speaking is only possible if the vocabulary has been precisely developed, if the elements are all in their proper place. Making good architecture is like learning to speak all over again. Everything that has already been said is fundamental; all the words already exist. So they do not have to be created in an inventive way, but employed in an intentional way. The result is new sentences, which emerge in conjunction with their grammar, and yet never - if done correctly - end up as complete nonsense.28

28 Geers, Kersten. 2013. “Intentions, Inventions.” OASE Journal For Architecture (nai010 publishers) (90): 12-13.

At Villa Buggenhout, the plainness of its 9-square plan offers a collapsed view of history wherein Andrea Palladio offers neither a rhetorical allusion (a la post-modernism), nor a reverential nostalgia (a la neo-classicism). Here, it is merely a strategy for a contemporary house to find resolution through a series of rooms. Two stories, each a variation of the 3x3 grid offers a particular set of rules to live by that correspond to the particular programs and question the subjectivity of a designer’s taste. On the ground floor, the cruciform squares of the 3x3 plan are enclosed while the outer corners form semi-enclosed terraces and exterior rooms opening onto the adjacent fenced-in yards. The legs of the cruciform comprise the entry vestibule, kitchen, dining room, and storage/bathroom. The ground floor seemingly lacks an exterior material, as it is either clad with glass doors or wire fence; but its interior is entirely lime-washed masonry units, with exposed concrete lintels marking the thresholds. The central square houses a spiral staircase leading to the upper level, which encloses the entirety of the 9-square module. The cladding of the upper volume is the same black PVC used for the roofing, forming an austere black box, punctuated by room-sized sliding glass windows facing the front and rear yards. The eight outer rooms on the upper level are three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a playroom, living room, and an office. On this “private” level, all of the interior walls are rotary cut plywood with a plywood ceiling with exposed joists. The almost embarrassing simplicity of the plan, the irrelevance of its reference, and the crudeness of its materials and detailing are subverted by the sensitive approach for how a family could live on its estate in a distinctly organized and integrated arrangement of rooms. Neutral and obstinate from outside of its fence, it opens into an economized world where the interior breathes life into its users through direct relation of one space to the next.

[Fig. 11]

Fig. 11

Villa Buggenhout Plans

Drawing by OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen

2012

http://officekgdvs.com/projects/#office-39

(accessed April 30, 2018)

[Fig. 12]

Fig. 12

Villa Buggenhout Exterior

OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen

Photo: Bas Princen

2012

http://officekgdvs.com/projects/#office-39

(accessed April 30, 2018)

Finally, the Dutch practice Studio Anne Holtrop, relies on the infinite interpretability of all things to provide the impetus for his architectural work. By drawing upon references or materials from outside the realm of architecture such as inkblots, topographic lines, or specific material processes, Holtrop seeks to find invention through the intuitive building upon each previous step of his process. With the material or image as its primary source, each step is taken without a preconception for where to go next, but rather as a direct, intuitive response from what was received.

I am interested in a possible architecture. In my work I start with form or material that often comes from outside architecture. In the conviction that things can always be re-examined and reinterpreted, they can also always be seen as architecture.