The following essay was written in Fall 2018 in partial fulfillment for coursework with Dr. Richard Shiff in the Art History Department at The University of Texas at Austin as part of a Master of Architecture focusing on Interdisciplinary Studies.

Beyond the Limit

Indeterminate Experience in the Work of Walter De Maria

Determine the limits of an object or event.

Determine the limits more precisely.

Repeat, until further precision is impossible.

-George Brecht, Exercise (1963)1

1 Eleey, Peter. "Thursday." In The Quick and the Dead, by Peter Eleey, edited by Peter Eleey, 31-55. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Walker Art Center, 2009.

Feeling to Thought

Thought to Feeling

Thought to Feeling

Feeling to Thought

-Walter De Maria2

2

Fukutake, Nobuko, Soichiro Fukutake, Yuji Akimoto, Tadao Ando, Romy Golan, Sebastian

Guinness, Walter De Maria, Paul Hayes Tucker, James Turrell, Hiroyuki Suzuki, Naoya

Hatakeyama, Ryuji Miyamoto. Chichu Art Museum: Tadao Ando builds for Walter De Maria,

James Turrell, and Claude Monet. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2005.

Confronting the work of Walter De Maria is perplexing. Critics and curators frequently characterize his work as mysterious or sublime, despite its eminently definable physical characteristics. Art historians insert his work among several disparate stylistic categories including Land Art, Conceptual Art, Fluxus, and Minimalism, which suggests that the essential nature of his oeuvre may be as indefinable as any single experience of one of his works. Any authoritative or conclusive statement about his work would be antithetical to the very quality that captivates the critics who praise it as enigmatic. Devoid of any signifier of the artist’s hand or prejudice, one may describe the objective qualities of the work – the material, the shapes and measurements of each object, the weight of those objects, the number of total objects, the number of like objects, the number of permutations, the distance between objects, the physical dimensions of the space in which the work is situated, etc. Faced with the dilemma of interpreting the work beyond mere description, one might rely on the titles of the works for insight into the meaning of the work. Often times, the title of the work provides an overview description for the viewer, as is the case with The Broken Kilometer, The Vertical Earth Kilometer, The New York Earth Room, or The 5-7-9 Series. Other times, De Maria employs a more evocative title such as The Beginning and End of Infinity, Time/Timeless/No Time, Seen/Unseen Known/Unknown, or Apollo’s Ecstasy. Other times still, his titles approximate a prosaic description, but veer into the conceptual, as is the case with The Lightning Field, High Energy Bar, or 360° I Ching.

Apart from a work’s form or title, an art historian might rely on biographical knowledge or artist statements for interpretive clues about the work. Born in 1935 in Albany, CA, Walter De Maria went on to study history and art at the University of California - Berkeley before moving to New York in 1960 to begin his career as an artist. Notoriously private – on the verge of being reclusive – De Maria only gave one extended interview in his career, in 1972 with Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art. For an art historian or critic seeking to extrapolate meaning from his work and communicate it to readers, the task proves nigh impossible. In De Maria’s work, whose contribution to the Fluxus precursor An anthology of chance operations... was titled “Compositions, Essays, Meaningless Work, Natural Disasters,” there is no discrete meaning to be found. There is no definitive interpretation or evaluation about the motive force of his work. There is only individual apprehension of the work, in which what can be known about the work is delimited by its precise physical characteristics – its structure. The fullest experience of Walter De Maria’s work comes to light when one confronts that limit and, through a process that adds nothing to a collective archive of knowledge, reckons with one’s own (ontological) sense of self, and stands at the doorstop of everything that lies beyond it.

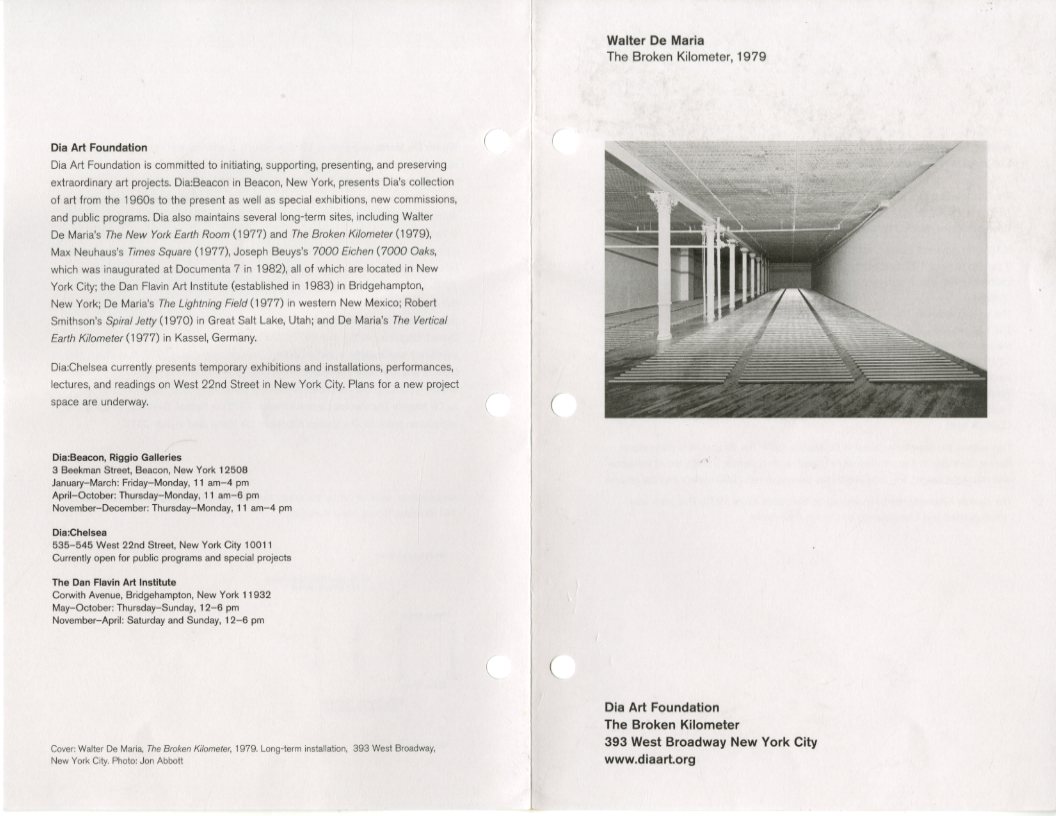

The brief passages included at the beginning of this essay may provide some insight into what happens when experiencing Walter De Maria’s work in its fullest capacity. First, a Fluxus contemporary of De Maria, George Brecht outlines the basic parameters for experience and creation, which could be applied to the confrontation with any thing, but in this instance the confrontation with the art objects authored by Walter De Maria. In the case of The Broken Kilometer [Fig.1], a site-specific installation in New York City, one determines the limits of the object by dealing with the boundaries of the space, abiding by the rules of the institution, and in experiencing the perceptual limitations of viewing a work from a single vantage point.

Fig. 1

Situated at 393 West Broadway, with an unassuming storefront, one walks in the door and is immediately faced with a white wall displaying nothing but the text:

Fig. 1

Walter De Maria

The Broken Kilometer

1979

Photo: Jon Abbott

Dia:

© The Estate of Walter De Maria.

https://diaart.org/visit/visit/walter-de-maria-the-broken-kilometer-new-york-united-states

Walter De Maria

The Broken Kilometer, 1979

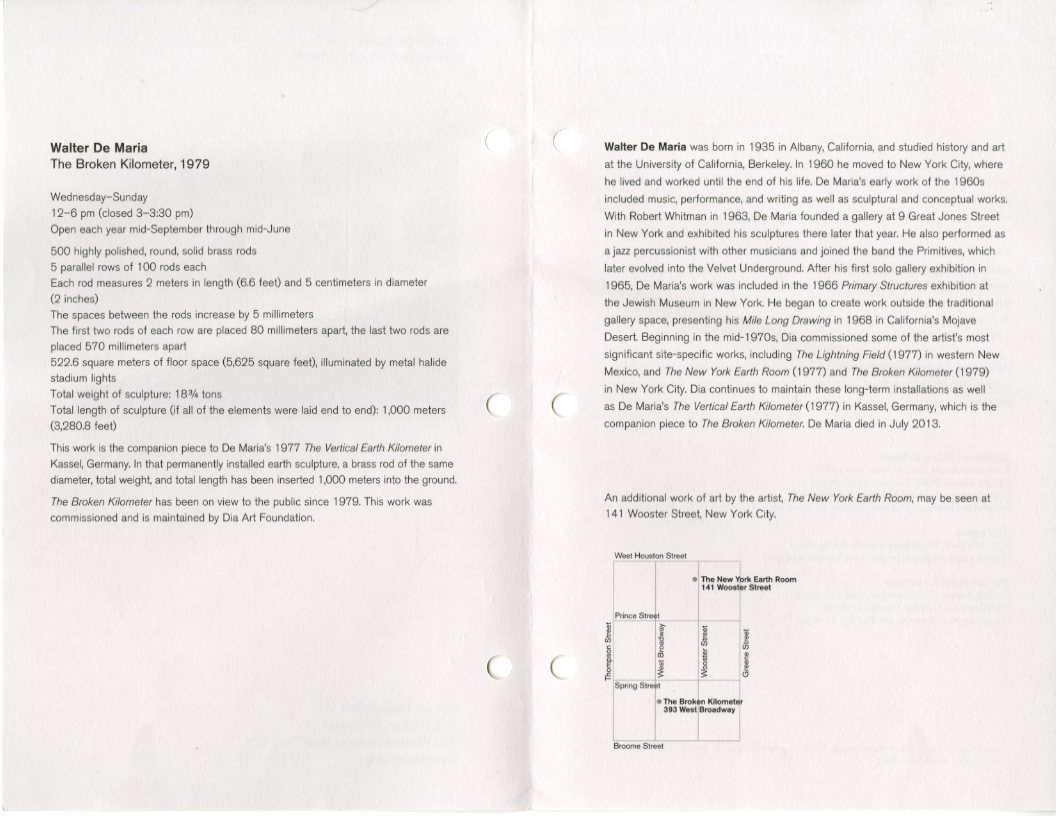

A dead end to the right, one moves instead to the left of the entrance where pamphlets detailing the work can be found [Fig. 2] and finally around the corner to where the actual sculpture resides. In the main space, a low barrier separates the intervention and demarcates a swath of floor about ten feet deep for visitors to traverse the width of the space. At the far right end of this foreground a docent sits at a desk to answer any questions. The room and work is illuminated by a series of linear fluorescent lights on the ceiling at the fore of the room, above the viewer, but out of sight, in a cove directed towards the back of the room in the same direction as the viewer’s gaze. Beyond the low barrier lies the primary content of the work: an array of 500 2-meter long brass rods, 5 centimeters in diameter, displayed in five parallel rows of 100 rods each, with each successive rod spaced farther apart than the previous rod in order to counteract perspectival diminution. The first two rods are spaced 80 millimeters apart; the last two, 570 mm apart. Because of the limitation on viewer engagement with the rods, one would not be able to scrutinize these dimensional aspects with a tape measure. Instead this information is provided in the pamphlet – a comprehensive and precise account of the physical properties of the space and the work. Much of the work to determine the limits of the installation has already been done prior to the viewer seeing the work. We have a conceptual understanding of size – as defined by human-devised “objective” measurement systems; but we can only perceptually apprehend and experience scale. The size is outlined for the viewer in the pamphlet, but not the scale which is the marker of firsthand experience. As in many art experiences, photography is prohibited. This detail is not insignificant in that it serves to not only preserve inasmuch as it is possible, the aura3 of the work, but also because it establishes a primacy of being in front of the work, in a body, reckoning with the scale of it firsthand – not merely its objectively communicable size. Mentally it is easy to conflate scale with size as we may have an idea of what a kilometer is – perhaps it is thought of as duration or in terms of time: “I can run a kilometer in x minutes & y seconds;” or perhaps in terms of its size as related to other known objects: “I can fathom the length of a kilometer because the entrance ramp to the highway I use is exactly one kilometer.” In either case though, the kilometer presents itself to us as a discernable whole unit of size only because at some point we have apprehended its scale through direct perceptual experience. Because of that experience, the connotation of the word kilometer holds meaning to us. By breaking it into smaller components, however, and still referring to it as a kilometer, the viewers (we) are left to question the culturally-habitualized meaning that we previously derived from the word. It is not incorrect to refer to 500 discrete rods each 2-meters in length as amounting to a kilometer, but we do not experience the kilometer in the way in which we have grown accustomed, namely as a whole, uninterrupted unit. For, if it is broken into smaller parts, what value or meaning can we derive from the (virtual) length of the whole? It no longer carries its objective purity and wholeness that gave it its facticity, and thus we are simply left with a broken kilometer – if it can still be called a kilometer at all. In questioning the meaning of that single unit, next we question the authority of the metric system in which it exists. De Maria primes us to this delimitation of our own conceptual systems in the pamphlet wherein the physical descriptions have been presented to the reader using two different standards (metric and imperial) as if the equivalent conversions held some additional nuanced significance to our comprehension of the piece.4 Instead, our ability to conceive of the broken rods as a kilometer relies on our mental capacity to feel the scale of their presentation and subsequently use our imagination to fill in the gaps. The anti-perspectival illusion demonstrated by the successively increasing rod spacing reinforces the instability wherein what we perceive aligns with our conceptions of space and the mental tools we use to describe it.

3 “The definition of the aura as a ‘unique phenomenon of a distance however close it may be’ represents nothing but the formulation of the cult value of the work of art in categories of space and time perception. Distance is the opposite of closeness. The essentially distant object is the unapproachable one. Unapproachability is indeed a major quality of the cult image. True to its nature, it remains ‘distant, however close it may be.’ The closeness which one may gain from its subject matter does not impair the distance which it retains in its appearance.”: Walter Benjamin, "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn, 217-251 (New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1969).

4 To speak for a moment on De Maria’s most well-known work, The Lightning Field, it is worth mentioning that the arbitrariness of measurement systems is apparent from the simple description of the piece’s size: one mile wide by one kilometer long. Here it is not simply a conversion that is offered, but two different systems used simultaneously to describe analogous features of the piece – its length and width – as though each needed to be described in the respective system’s units.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Scan of pamphlet

The Broken Kilometer

Obtained from site, April 2016.

Brecht’s Exercise outlines the work that must be done in order for one to be subject to the effects of the installation. One cannot simply arrive at one of De Maria’s projects expecting a transcendental experience. Effort must be applied to the apprehension of the piece so that one can undergo the mental preconditioning necessary to appreciate it. Once the effort has been offered, and the determination of the limits of the piece has been independently arrived at, De Maria’s chiastic words at the top of this essay can take hold. In true De Maria fashion, the permutative limits of the reciprocal word structure have been presented through a double chiasmus – the relationship between feeling and thought has been exhausted, much like the numerical sequence projects such as the 4-6-8 Series, 5-7-9 Series, 3-4-5 Series in which every possible mathematical sequence of the three different objects are exhibited in full. With three distinct “types” of object, there are 27 possible sequential variations in which all three can be exhibited. The exhibition of all its permutations prompts us to acknowledge the objects as a closed set: there are no additional possibilities, and so it is offered to us as whole, complete, unified, and perfect. In its wholeness presented as such, its discernability gives rise to the impression that everything that can be known about the group of objects is known. As Clement Greenberg eloquently puts it,

“Science has

told us nothing about the absolute ground of being, and I can well see how, in

view of this, some people might find superficial the sureness and clarity that

science displays in treating what is knowable.

The knowable, that about which verifiable propositions can be formulated, may

strike them as shallow simply because it can be known… But in the name of

‘profundity’ we still long to dissolve our art and ourselves in some ultimate

vagueness or confusion.”5

5 Greenberg, Clement. Religion and the Intellectuals: A Symposium. Vol. III, in Clement Greenberg:

Collected Writings, 39-42. Partisan Review, 1950.

If the knowable

is trite, then this perfect whole would offer nothing of import to the viewer.

For the viewers who accept this, two choices are presented: Either to move on,

regarding the entire piece as trite, or to continue to seek out something which

is seemingly unknown. For the latter

viewer, when no additional “facts” can be ascertained, the inquisition becomes

formless. It is not simply a matter of collecting additional data - for the

system is already whole - but rather to engage in the conceptual functions that

De Maria outlines for us in the passage. Thus, once the objects’ limits have

been determined and defined to their absolute limit (until further precision is impossible), we are left with an abyss in

which our own minds vibrate from feeling to thought and back again (and forth

again). This experience – an oscillation of feelings and thoughts as provoked

by our being in front of and reckoning with the scale of his works – is perhaps

what other critics have meant when they describe his work as belonging to the sublime.

It is difficult to communicate clearly and effectively about the nuances of feeling(s). To attempt it at all is – in Charles Sanders Peirce’s terms – to come too late, “… it is plain enough that all that is immediately present to a man is what is in his mind in the present instant. His whole life is in the present. But when he asks what is the content of the present instant, his question always comes too late.”6 However, in the spirit of philosophical inquiry such an attempt is necessary to briefly explore the concept of the sublime. Without delving into the scholarship on sublimity too deeply (it is far beyond the scope of this essay and has already been investigated ad nauseam), it is still necessary to propose that the use of the word sublime as an adjective to describe a singular feeling or to characterize a particular quality of an object is perhaps misguided. Immanuel Kant came close when he described the sublime as a mental attunement to our own imagination’s capacity to exhibit ideas beyond its own scope of comprehension. “Hence, what is to be called sublime is not the object, but the attunement that the intellect (gets) through a certain presentation that occupies reflective judgment. Hence we may supplement the formulas already given to explicate the sublime by another one: Sublime is what even to be able to think proves that the mind has a power surpassing every standard of sense.”7 Rather than a signifier for a particular feeling instigated by the visual recognition of a thing’s scale, the sublime instead may refer to a magnitude or intensity of many feelings (of which wonder and awe may be components), as contrasted to those parts of our being preoccupied with thinking. In other words, the sublime may simply be an absolute indeterminacy between feeling and thought – a circumstance in which one feels (Peirce’s firstness), however fleeting it may be, a chaos of “feelings” indescribable and inconceivable with such intensity as to suppress all cognitive functions of recognition, relationality, intellect, or other mental processes akin to Peirce’s secondness or even thirdness, only to oscillate back into thinking, comprehension, rationality, and self-awareness. Peirce, critical of Kant’s separate assertions about the manifold nature of sense, breaks this process into two separate but inextricable processes, firstness and secondness. “On the whole, the Second must be reckoned as an easy conception. It is the main lesson of life. The first is too tender an idea to be laid hold of without destroying it; the slightest admixture of the idea of second renders it no longer the positive first. But the second is hard and tangible, and an admixture of firstness, far from destroying it, is a necessary ingredient of it.”8 The sublime is not a quality of the object itself, but rather a condition of experiences aroused in a viewer in which he/she concurrently feels wonder, awe, mystery, fear, excitement, possibility, ecstasy, and other momentarily discernible feelings that are actually (during the experience of sublimity) not discernible at all, to such a degree that the mixture of feeling overcomes one’s thought and conception about his/her being in that place and time, only to heighten the very cognitive function that makes the user self-aware in his/her own humanity: that is to think, as rational beings. Thus the sublime seems to be an intense amalgam of indeterminate and constantly shifting mental functions in the viewer: pure chaos as manifested in the constant interplay between feeling and thought. It is, perhaps, the durational interplay of first and second. “We are forced to acknowledge our limitations, but in the drunken dream of our immediate feeling we remain gods. Secondness, limitation, death, is something that we must admit but can never realize.”9 The experience of the sublime would need to operate at the limits of human experience: an unstable link that connects our own sense of mortality with that which lies beyond. The quality of an art object’s capacity to elicit such a condition in us could be deemed its potency.

It is difficult to communicate clearly and effectively about the nuances of feeling(s). To attempt it at all is – in Charles Sanders Peirce’s terms – to come too late, “… it is plain enough that all that is immediately present to a man is what is in his mind in the present instant. His whole life is in the present. But when he asks what is the content of the present instant, his question always comes too late.”6 However, in the spirit of philosophical inquiry such an attempt is necessary to briefly explore the concept of the sublime. Without delving into the scholarship on sublimity too deeply (it is far beyond the scope of this essay and has already been investigated ad nauseam), it is still necessary to propose that the use of the word sublime as an adjective to describe a singular feeling or to characterize a particular quality of an object is perhaps misguided. Immanuel Kant came close when he described the sublime as a mental attunement to our own imagination’s capacity to exhibit ideas beyond its own scope of comprehension. “Hence, what is to be called sublime is not the object, but the attunement that the intellect (gets) through a certain presentation that occupies reflective judgment. Hence we may supplement the formulas already given to explicate the sublime by another one: Sublime is what even to be able to think proves that the mind has a power surpassing every standard of sense.”7 Rather than a signifier for a particular feeling instigated by the visual recognition of a thing’s scale, the sublime instead may refer to a magnitude or intensity of many feelings (of which wonder and awe may be components), as contrasted to those parts of our being preoccupied with thinking. In other words, the sublime may simply be an absolute indeterminacy between feeling and thought – a circumstance in which one feels (Peirce’s firstness), however fleeting it may be, a chaos of “feelings” indescribable and inconceivable with such intensity as to suppress all cognitive functions of recognition, relationality, intellect, or other mental processes akin to Peirce’s secondness or even thirdness, only to oscillate back into thinking, comprehension, rationality, and self-awareness. Peirce, critical of Kant’s separate assertions about the manifold nature of sense, breaks this process into two separate but inextricable processes, firstness and secondness. “On the whole, the Second must be reckoned as an easy conception. It is the main lesson of life. The first is too tender an idea to be laid hold of without destroying it; the slightest admixture of the idea of second renders it no longer the positive first. But the second is hard and tangible, and an admixture of firstness, far from destroying it, is a necessary ingredient of it.”8 The sublime is not a quality of the object itself, but rather a condition of experiences aroused in a viewer in which he/she concurrently feels wonder, awe, mystery, fear, excitement, possibility, ecstasy, and other momentarily discernible feelings that are actually (during the experience of sublimity) not discernible at all, to such a degree that the mixture of feeling overcomes one’s thought and conception about his/her being in that place and time, only to heighten the very cognitive function that makes the user self-aware in his/her own humanity: that is to think, as rational beings. Thus the sublime seems to be an intense amalgam of indeterminate and constantly shifting mental functions in the viewer: pure chaos as manifested in the constant interplay between feeling and thought. It is, perhaps, the durational interplay of first and second. “We are forced to acknowledge our limitations, but in the drunken dream of our immediate feeling we remain gods. Secondness, limitation, death, is something that we must admit but can never realize.”9 The experience of the sublime would need to operate at the limits of human experience: an unstable link that connects our own sense of mortality with that which lies beyond. The quality of an art object’s capacity to elicit such a condition in us could be deemed its potency.

6 Peirce, Charles S. A Definition of Feeling. Vol. I, in Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, by Charles S. Peirce, edited by Charles and Paul Weiss Hartshorne, 152-155. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1960.

7 Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgment. Translated by Werner S. Pluhar. Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987.

8 Peirce, Charles S. "First, Second, Third." In Writings of Charles S. Peirce: A Chronological Edition, Volume 5: 1884-1886, by Charles S. Peirce, edited by Christian J.W. Kloesel, 302-308. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993. p.305.

9 Ibid.

Art objects – like

all objects – have varying degrees of potency, which could be posited as one

measure of a work’s quality. From the Latin root potentia, denoting power, potency shares its origin with a more

commonly used term: potential. One may understand potential broadly as the

latent possibility for an event to occur. Potency would be the power or

magnitude with which the event – or merely the possibility of the event – would

affect one’s mind and/or body. This root word, potentia speaks to another quality often used to describe the

content of De Maria’s work – energy. Primary school science class tells us that

all objects have some degree of potential energy – that is the capacity to act. Its counterpart, kinetic energy, is used to describe an object when it is in

movement, or in the midst of enduring an event. As the kinetic energy of an

object increases, its potential energy decreases. Inversely proportional, the

theory maintains that an object always contains within itself a constant amount

of energy, only the type of energy shifts. This conservation of energy – that

energy can neither be created nor destroyed – is merely another description we

use, not necessarily offering us a truth, but only a conventional understanding

of the world around us. Still, it serves to illustrate that the static objects

of De Maria – in all their precision and formal purity – contain within them a

maximum amount of potential energy. All objects have potential energy though.

De Maria implies the importance of energy through a paradoxical relationship

with its seemingly formal perfection. This illusion of perfection suggests that

despite the great effort and machine precision given to the creation of the

objects, perfection is unattainable and delicate. The objects’ reproducibility

may be granted by technology, but the degree of precision required to make 500

identical brass rods is inconceivable in its impossibility. In speaking about

signatures, Jacques Derrida offers some insight into reproducibility and the

nature of possibility, “This is the

enigmatic originality of every paraph. For the attachment to the source to

occur, the absolute singularity of an event of the signature and of a form of

the signature must be retained: the pure reproducibility of a pure event… The

condition of possibility for these effects is simultaneously, once again, the

condition of their impossibility, of the impossibility of their rigorous

purity.”10 There could be a meaningless iconographic study used to illustrate that De

Maria’s metal rods signify energy, but the point being made here is to place

energy under the purview of potency,

which asserts nothing of meaning but rather paradoxically, through its precise

formal realizations, contains a capacity towards indeterminacy. Once again,

according to Derrida, “There is no metaphysical concept in and of itself. There

is a work – metaphysical or not – on conceptual systems. Deconstruction does

not consist in passing from one concept to another, but in overturning and

displacing a conceptual order, as well as the nonconceptual order with which

the conceptual order is articulated.”11 There is no meaning or concept behind De Maria’s Broken Kilometer, only the impulse towards a question: Faced with

the rods’ impossibly rigorous purity, at the recognition of a system of

measurement that no longer offers reliable knowledge, what is?

The operative function through which one reckons with an object’s potency is through bodily relation; that is through the scale of the object as apprehended by firsthand perceptual experience. Scale is the most essential method through which we apprehend an object’s potency because, unlike other perceptual or sensory capacities, acknowledging the scale of an external thing implicitly mandates the acknowledgement and awareness of one’s own body – it is physiological by definition, requiring both intellect and bodily presence. Only through a mental conception of the body that contains one’s mind can the scale of something external be relatable. One does not simply see (visually recognize) a thing’s scale. Through photographs one can register a cursory understanding of relationships through the scale of one object depicted next to another, but that knowledge is subject to photographic and perspectival trickery, and because of the auratic translation inherent in all photographs, it cannot elicit an innate understanding of how a thing relates to one’s own body. One feels scale because its apprehension begins with an intuitive understanding of one’s bodily presence in the world and one’s bodily parameters as compared to the external object that shares a perceptual field.

An uncertain proclamation: if De Maria’s work is about anything, it is about dimension; not in the narrow sense of providing a measure for the thing, but about the dimensions in which the thing exists spatially, temporally, and mentally. Dimension is the umbrella in which subject and object both exist; it is everything. To suggest that his work, if it is about anything at all, is about everything illustrates exactly the tension and oscillation present in registering an object’s potency. Scale is our mediator of dimension – we conceive of and apply rational systems (scales) to our reality in order to measure experience. Tapes and rulers measure distance and size, scales and magnets measure gravitational forces, while clocks and calendars measure the passing of time. The readouts do not explain anything about our world, as they only contain meaning for us insofar as they allow us to describe a thing’s properties in order to communicate with others who share a presence in our dimension. Friedrich Nietzsche writes, “Cause and effect. – ‘Explanation’ is what we call it, but it is ‘description’ that distinguishes us from older stages of knowledge and science. Our descriptions are better–we do not explain any more than our predecessors.” With De Maria, one only describes the work in its manifold physical measures, offering no additional explanation of technique or origin – a decidedly Structuralist methodology, which is perhaps why he did not hold a high regard for art criticism or theories about his work. Nietzsche continues, “But how could we possibly explain anything? We operate only with things that do not exist: lines, planes, bodies, atoms, divisible time spans, divisible spaces. How should explanations be at all possible when we first turn everything into an image, our image!”12

The operative function through which one reckons with an object’s potency is through bodily relation; that is through the scale of the object as apprehended by firsthand perceptual experience. Scale is the most essential method through which we apprehend an object’s potency because, unlike other perceptual or sensory capacities, acknowledging the scale of an external thing implicitly mandates the acknowledgement and awareness of one’s own body – it is physiological by definition, requiring both intellect and bodily presence. Only through a mental conception of the body that contains one’s mind can the scale of something external be relatable. One does not simply see (visually recognize) a thing’s scale. Through photographs one can register a cursory understanding of relationships through the scale of one object depicted next to another, but that knowledge is subject to photographic and perspectival trickery, and because of the auratic translation inherent in all photographs, it cannot elicit an innate understanding of how a thing relates to one’s own body. One feels scale because its apprehension begins with an intuitive understanding of one’s bodily presence in the world and one’s bodily parameters as compared to the external object that shares a perceptual field.

An uncertain proclamation: if De Maria’s work is about anything, it is about dimension; not in the narrow sense of providing a measure for the thing, but about the dimensions in which the thing exists spatially, temporally, and mentally. Dimension is the umbrella in which subject and object both exist; it is everything. To suggest that his work, if it is about anything at all, is about everything illustrates exactly the tension and oscillation present in registering an object’s potency. Scale is our mediator of dimension – we conceive of and apply rational systems (scales) to our reality in order to measure experience. Tapes and rulers measure distance and size, scales and magnets measure gravitational forces, while clocks and calendars measure the passing of time. The readouts do not explain anything about our world, as they only contain meaning for us insofar as they allow us to describe a thing’s properties in order to communicate with others who share a presence in our dimension. Friedrich Nietzsche writes, “Cause and effect. – ‘Explanation’ is what we call it, but it is ‘description’ that distinguishes us from older stages of knowledge and science. Our descriptions are better–we do not explain any more than our predecessors.” With De Maria, one only describes the work in its manifold physical measures, offering no additional explanation of technique or origin – a decidedly Structuralist methodology, which is perhaps why he did not hold a high regard for art criticism or theories about his work. Nietzsche continues, “But how could we possibly explain anything? We operate only with things that do not exist: lines, planes, bodies, atoms, divisible time spans, divisible spaces. How should explanations be at all possible when we first turn everything into an image, our image!”12

10 Derrida, Jacques. "Signature Event Context." In Margins of Philosophy, by Jacques Derrida, translated by Alan Bass, 307-330. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1971.

11 Ibid. 329

12 Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1974.

In

his theory of the sublime, Immanuel Kant offers two distinct orders of its experience

– that of the mathematical sublime, and of the dynamically sublime. In Time/Timeless/No Time [Fig. 3], if you

deem the sculpture to have potency, then your experience may appeal to both

types of the sublime. To experience the mathematically sublime, one undergoes

the aforementioned process of apprehending the closed set of triangular, square

and pentagonal prism combinations. Displayed at various heights and locations

in the space, the seemingly equivalent sequences exhibit a false (arbitrary) hierarchy.

Despite one’s sensory impulses to attribute hierarchy to the individual triads,

the recognition of the entire set as complete and internally equivalent

reasserts its arbitrariness and meaninglessness. Kant’s theory of the

mathematically sublime suggests that it is rooted in confronting numbers

unfathomable or incomprehensible by our imagination, but in doing so we become

attuned to the presence of our imagination as rational beings. The whole set –

in its blatant fathom-ability – becomes open ended when acknowledging that

sequences themselves are open ended. A three-sided shape, a four-sided shape,

and a five-sided shape are presented here together in each possible distinct

arrangement of the terms. What we understand as belonging to an ascending order

of numerical counting is instead a discrete selection of an infinite number of

sequences. Only the recognition of the (false) wholeness of the set prompts an

inquiry into the infinite possibilities that lie beyond it.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Walter De Maria

Time/Timeless/No Time

from the 3-4-5 Series.

2004

Image from Chichu Art Museum: Tadao Ando builds for Walter De Maria, James Turrell, and Claude Monet (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2005).

In the case of the dynamically sublime, which Kant claims belongs to nature’s ability to exert its infinite might over you, the process of arriving at or near the sublime is the more affecting type, as it deals with direct, perceptual scale. “We cannot determine this idea of the supersensible any further, and hence we cannot cognize but can only think nature as an exhibition of it. But it is this idea that is aroused in us when, as we judge an object aesthetically, this judging strains the imagination to its limit, whether of expansion (mathematically) or of its might over the mind (dynamically).”13 The green granite sphere at the mid-landing measures 2.2 meters in diameter and weighs 17 tons. Unlike most art experiences, the museum docents encourage interaction with the sphere. A ball is perhaps the first and most common illustration of potential energy that one can grasp. When thrown straight up into the air, the ball reaches its apex, and in that instant contains a maximum amount of potential energy. That instant is the threshold between the expenditure of the force required to throw it straight up, and the downward force of gravity acting against it. A ball at the top of the stair would suggest that its desire is to accept gravity’s pull and to descend. Viewers put all their weight and force against it only to come to terms with their physical limitations and thus the immensity of its mass to exist beyond what they could affect without the aid of additional technology. The ball does not descend the staircase. Its position in the middle though, suggests that there was an initial gesture to place it there – it either ascended the lower flight, or descended the upper one in order to lie in the middle. Despite its stillness, its position implies that it had kinetic energy in its recent past. The potential energy is now at its maximum, seemingly ready to be acted upon, but perpetually resisting us – despite the utmost application of our might. The feeling of defeat or impotence following this effort gives the piece its potency. The space – a vaulted ceiling, lit only at the top by a skylight piercing a dropped ceiling in which light floods its perimeter – shares formal similarities to religious spaces of antiquity; flights of stairs leading to temples or places of worship at heights that only deities could reside. As time passes though, the direction of the light changes – a visual recognition of duration [Fig. 4]. In recognizing the changing light both as the movement of light rays and shadows across the walls, as well as in the sphere’s constantly shifting reflectivity, time and space are made manifest. Reflections of oneself would typically suggest a kind of narcissism, but in the case of being reflected on a constantly shifting round surface – following the feeling of one’s own impotence – and viewing the mathematically delimited gold polygonal rods in direct apprehension and indirect reflection instead establishes one’s bodily insignificance and thus, if the mind has been preconditioned by exhausting its comprehensive limits, one could experience the dynamically sublime. “That which shows itself and at the same time withdraws is the essential trait of what we call the mystery… If releasement toward things and openness to the mystery awaken within us, then we should arrive at a path that will lead to a new ground and foundation.”14 The confrontation of the mysterious illuminates one’s ground of being by exposing our inability to exist or comprehend anything beyond this realm. In grounding the viewer’s being, he/she is shown that this land, the earth, and everything we understand as belonging to our ground takes primacy.

13 (Kant 1987, p. 128.)

14 Heidegger, Martin. "Memorial Address." In Discourse on Thinking, by Martin Heidegger, translated by John M. and E. Hans Freund Anderson, 43-57. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1966.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Walter De Maria

Time/Timeless/No Time

from the 3-4-5 Series.

2004

Image from Chichu Art Museum: Tadao Ando builds for Walter De Maria, James Turrell, and Claude Monet (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2005).

Walter De Maria

Time/Timeless/No Time

from the 3-4-5 Series.

2004

Image from Chichu Art Museum: Tadao Ando builds for Walter De Maria, James Turrell, and Claude Monet (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2005).

It

is impossible to speak about Walter De Maria without mentioning his association

with the Land Art Movement of the late 1960s. It would be equally impossible to

speak of Land Art without recognizing De Maria’s pivotal role in its inception.

But far from addressing the importance of that movement, it will serve us to

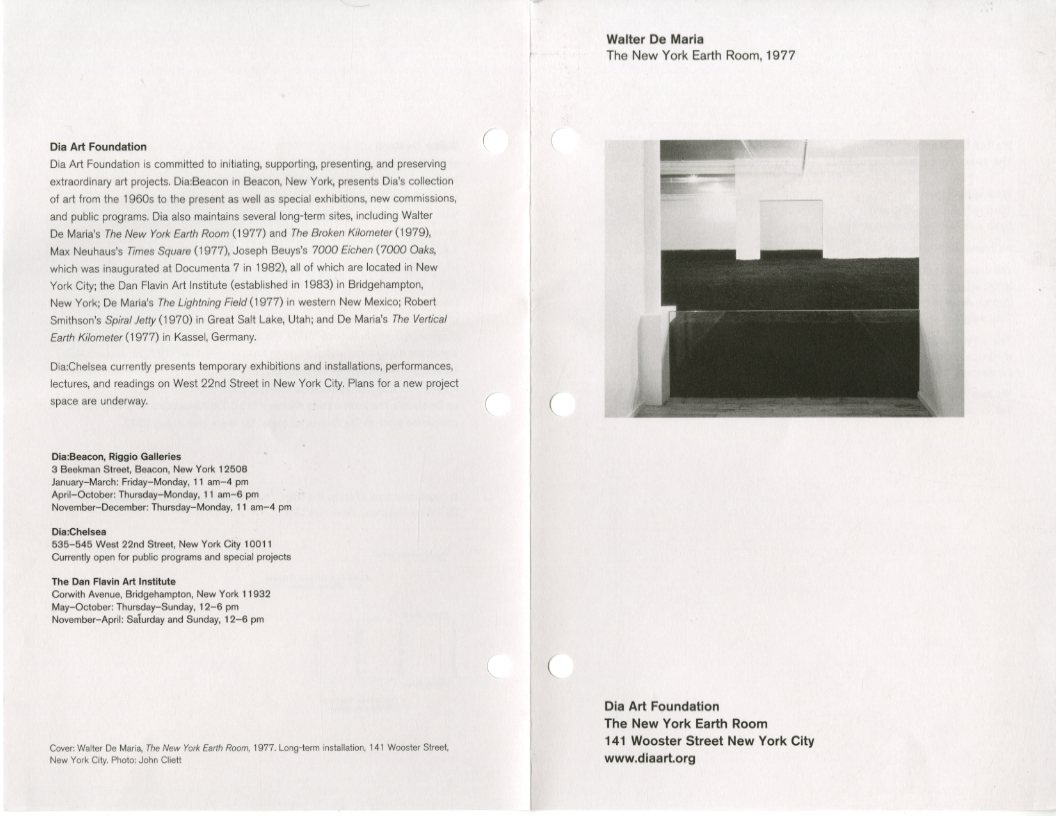

look at one of his more notable extant “Land Art” works, The New York Earth Room [Fig. 5]. Situated at 141 Wooster Street in

New York City, the room is only two blocks north and one block East of The Broken Kilometer.

![]()

Fig. 5

The difference between these works is stark, but ultimately serve the same concerns, seeking not to provoke a defined set of experiences, but instead to prompt an oscillation between first and second – feeling and thought – that would enable viewers to work towards re-establishing a mindfulness of their terrestrial nature. To enter the building off Wooster Street, one simply buzzes the intercom during regular visiting hours and is granted access to the stairwell leading up to unit 2B, where the sculpture resides. It is impossible to adequately convey in writing the smell with which one is hit upon entering the building off the street: a burst of peaty, organic, earthy must contrasts sharply from the olfactory cacophony of car exhaust, pollution, and wafting odors of food and human activity in the streets of New York City. Walking up a windowless fire egress staircase in order to arrive at unit 2B is a mundane experience, were it not for the smell of the mass quantity of dirt that (one knows) lies ahead. The sculpture lacks subtlety, though it retains the ambiguity necessary for indeterminate experiences of the sort described above. The ambulatory space is not dissimilar from The Broken Kilometer: there is a docent at a desk, there is a low barrier separating the viewer from the content of the sculpture, and a pamphlet [Fig. 6] is available to describe all the quantifiable information about the sculpture. In this case, the barrier is a short glass panel sandwiched between two walls retaining all the dirt that lies beyond it, rising to around knee height.

Fig. 5

The difference between these works is stark, but ultimately serve the same concerns, seeking not to provoke a defined set of experiences, but instead to prompt an oscillation between first and second – feeling and thought – that would enable viewers to work towards re-establishing a mindfulness of their terrestrial nature. To enter the building off Wooster Street, one simply buzzes the intercom during regular visiting hours and is granted access to the stairwell leading up to unit 2B, where the sculpture resides. It is impossible to adequately convey in writing the smell with which one is hit upon entering the building off the street: a burst of peaty, organic, earthy must contrasts sharply from the olfactory cacophony of car exhaust, pollution, and wafting odors of food and human activity in the streets of New York City. Walking up a windowless fire egress staircase in order to arrive at unit 2B is a mundane experience, were it not for the smell of the mass quantity of dirt that (one knows) lies ahead. The sculpture lacks subtlety, though it retains the ambiguity necessary for indeterminate experiences of the sort described above. The ambulatory space is not dissimilar from The Broken Kilometer: there is a docent at a desk, there is a low barrier separating the viewer from the content of the sculpture, and a pamphlet [Fig. 6] is available to describe all the quantifiable information about the sculpture. In this case, the barrier is a short glass panel sandwiched between two walls retaining all the dirt that lies beyond it, rising to around knee height.

Fig. 5

Walter De Maria

The New York Earth Room

1977

Photo: Jon Cliett

© The Estate of Walter De Maria. <http://diaart.org/visit/visit/walter-de-maria-the-new-york-earth-room-new-york-united-states/page/1>

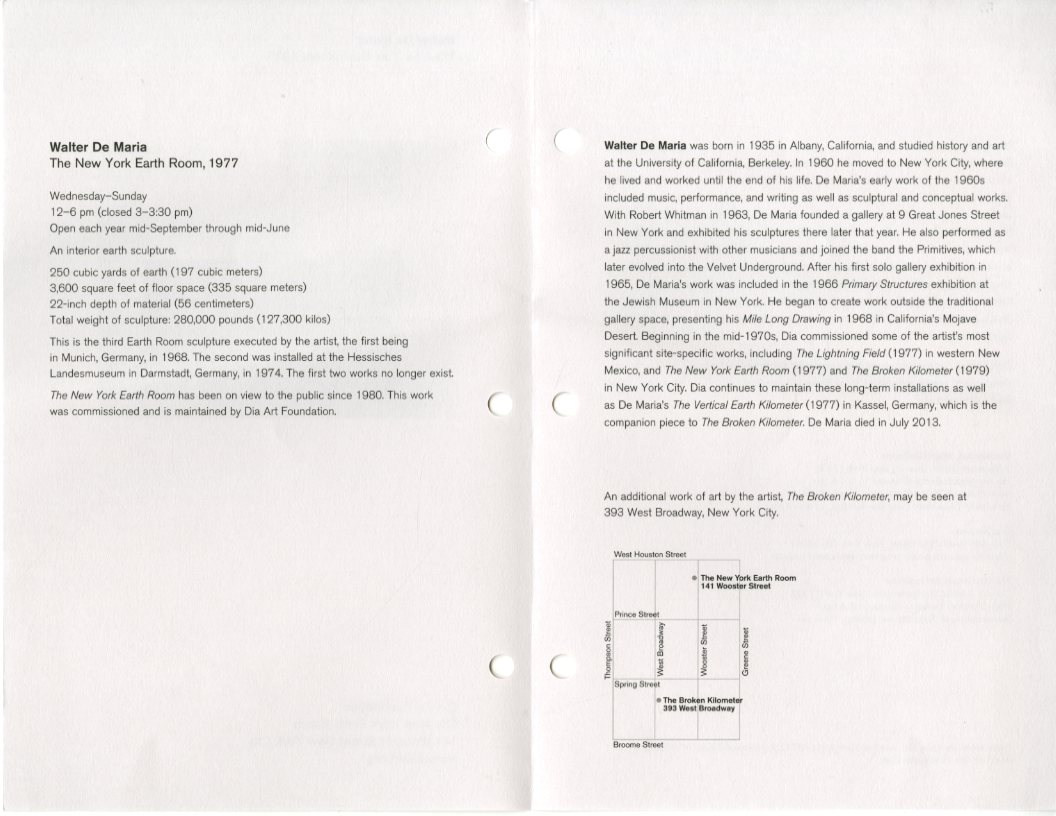

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Scan of pamphlet

The New York Earth Room

Obtained from site, April 2016.

One notable difference in the information available in the pamphlet takes the form of a brief sentence, “An interior earth sculpture.” It is unclear if the institution responsible for commissioning and maintaining the work, Dia Art Foundation, or the artist himself provided this statement. Either way, the notion that one could interiorize earth is a confounding one and prompts the question of how much “earth” would be required to do such a thing or what would the parameters of the space have to be to encapsulate that idea? Aside from the most obsessive compulsive among us, tracking dirt into our own places of residence is a common occurrence, though in much smaller quantities. De Maria reverses that relationship, providing 250 cubic yards of earth in 3600 square feet of floor space. Dirt, not furnished habitable space, becomes the content of this loft unit. As confined by the perimeter walls, the dirt rises to a depth of 22 inches. The total weight of the sculpture is listed as 280,000 pounds (127,300 kilos). Volume is a peculiar description to consider. It is perhaps the single most comprehensive description of an object’s space-taking, but most people probably do not have an intuitive sense of what it means. For example, when I think of a table, I think of its height, width, and length as discrete measures that enable me to imagine the space it takes up. When I think of other people, I imagine (among other things) their height and approximate weight. I cannot understand how much space a person occupies if it is conveyed to me in cubic inches. But in dealing with mass quantities of any substance, cubic volume is the most direct measure to communicate and cubic yards (NOT cubic feet) are the de facto unit used to convey amounts of earth. But unless one holds specialized knowledge from regularly moving or working with large quantities of earth, a cubic yard is a relatively meaningless unit. Without the memory of a previous experience or a common cultural inference to draw upon about the scale of a cubic yard (much less, 250), one does not have the sort of ‘baggage’ to exhaust in order to arrive at an authentic experience of its scale. Instead of a culturally-determined measure of size or the system in which that measure exists, the limits to be determined about The New York Earth Room, are in regards to the room itself.15 It is unclear whether 250 cubic yards of earth as the proper amount was decided upon arbitrarily, if it was informed by the bearing capacity of the floor framing and structure of the building, or if it was determined by the room’s dimensions. The level of the dirt is virtually in line with the windowsills on the Wooster Street side of the loft, thus suggesting a maximum height up to which the earth could be filled before breaking the glass and spilling through the windows and onto the street below. Another limitation of the room to consider is the wall’s capacity to withstand the weight of the earth. Although one can only stand behind the glass divider, peaking around the corner reveals that on the adjacent wall, the weight of the earth has bowed the surface cladding (gypsum wall board – sheetrock – most likely) where it spans between the studs used to frame the wall. [Fig.7] While this is perhaps unintentional on De Maria’s part, the concave undulations of a wall surface that one expects to be relatively free of deformities exhibits an uncertainty about the building’s ability to accommodate the earth being displayed. In truth, it is simply a matter of inadequate blocking in the wall and would pose no real threat to the building’s structural integrity. However, any doubt about the structure’s ability to do its job is to express a possibility of catastrophe.

Fig. 7

The earth is dark and appears soft and primed for cultivation, but – while one typically recognizes ‘earth’ as our ground, a surface to be walked upon – visitors cannot touch or enter the work. A visitor’s understanding of scale in this work is not interpreted through interaction or through conceptual measuring systems, but rather a ritualized understanding of the parameters of our dwelling places. Architects have supplied theories about scale for centuries – ranging from the well-known work by Leon Battista Alberti, Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Le Corbusier’s Modulor to the more obscure theories such as Dom Hans Van Der Laan’s Plastic Number. Yet the architectural scale at work here is not an esoteric theory about proportion as a qualifier for some ideal beauty, but rather an understanding of our own scale as it pertains to the architecture we occupy on a daily basis. A dwelling unit, be it a loft, apartment, or a house is principally defined by its outer walls (its limits). They reserve and appropriate space for furnishings, appliances, and decoration, also leaving ample room for circulation and human activity. Any notion of a single substance filling the confines of a house is usually associated with elemental catastrophe – as in flooding water in a basement, or a fire engulfing an entire floor of a house. The scale of any substance that could fill the dwelling unit to its perimeter walls would render its function as a place of habitation useless. Associations with immense quantities of earth are grave, connoting thoughts of earthquakes, landslides and burials. But those associates also contain wonder and promise, as in a garden bed, breaking ground for a construction site, or the site of archaeological discovery. Here it is unclear whether the confrontation of the earth should give way to promise and hope, or to peril and despair. But the recognition of a subdivided room in the loft in front of the viewer [Fig. 5], the earth permeating through its opening and out of sight provides a feeling of mystery. Maybe nothing is happening around the corner of that wall where I cannot see. But maybe also the dirt is deforming the wall to the brink of collapse or gently yielding sprouting plants or saplings. A small handful of dirt may not present these possibilities (for then it is only a nuisance related to cleanliness), but only confronting the magnitude of the displaced earth in this loft can one reckon with the mystery of its possibility. The potential for the building to fail under the pressure of the earth becomes as apparent as the innate potential of the dirt’s associations with fertility as earth.

15 In hindsight to writing the bulk of this essay, it is perhaps obvious that the qualities to consider and limits to determine about his various works of art may be given to us by the title of the work being considered. With The Broken Kilometer, the limit to be determined is our understanding of the measure, a kilometer. With The New York Earth Room, the limits to be determined are the capacity of the room to contain earth, and its function as a room.

Fig. 7

Walter De Maria

The New York Earth Room

1977

Source: Faber689, “The New York Earth Room.” October 2013, digital image.

Accessed via TripAdvisor

While

potency is related to power and potential in the manner described above, it

would be irresponsible not to mention the more colloquial use of the term – the

sexual capacity of a male to fertilize a female’s egg. The significance found

in a being’s ability to give life cannot be understated and, although it is not the principle definition in this

analysis, affords some insight into why the term carries relevance. The notion

that an artwork has potency and could

therefore give life is absurd. But

giving life is probably the single act that we can enact that exhibits wonder,

mystery, and awe on the scale of that which lies beyond us. In her book On Beauty and Being Just, Elaine Scarry

defends and asserts beauty as being life-affirming. She addresses the

bifurcation of the aesthetic realm into the sublime and the beautiful by late

eighteenth century philosophers such as Kant and Edmund Burke (to which Kant

repeatedly pays respect in his own treatise), and outlines how each term had

been subsequently characterized. “In the newly subdivided aesthetic realm, the

sublime is male and the beautiful is female…. The sublime is night, the

beautiful day. ‘the sublime moves’ (one

becomes ‘earnest… rigid… astonished’). ‘Beauty charms.’”16 It would be an easy mistake to place the sublime and the beautiful on opposite

ends of the aesthetic spectrum. One does not mutually exclude the other, for

many aspects associated with the beautiful (perfection, symmetry, wholeness,

etc…) are equally evident in De Maria’s work. But if the sublime is a mental

attunement, and not a quality of the object itself, it can be suggested that

our notion of what is ‘beautiful’ is simply a separate mental attunement. The

aesthetic trope that “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” thus takes on a

new meaning. Rather than advocating for a widespread acceptance of subjectivity

as we apply judgments to objects in our perceptual field, experiencing beauty

may have very little to do with the objects themselves. In that instance, if

the sublime is indeterminate and vibratory, then the beautiful must come forth

in experiencing clarity, restfulness, and equilibrium. It is possible that even

if one experiences the sublime in Walter De Maria’s work, it is likely that

pure oscillatory chaos of feeling and thought does not pervade the entire

experience. Moments of clarity and rest are inevitable, but perhaps equally

fleeting. Only a prolonged state of clarity would be determinable by its

ability to be described, though it would come too late. Perpetual clarity would

not be possible. Our nature as mortal beings gives even the strongest feeling a

temporal dimension. Thus, its finitude as a feeling implies an equal amount of

indeterminacy: clarity or a mental attunement towards the beautiful would eventually end and another experience would take

hold.

16 Scarry, Elaine. On Beauty and Being Just. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999. p. 83

Indeterminacy

would seemingly characterize all of our experiences. An object’s potency lies

in its ability to make us aware of our essential indeterminacy. “There, that by

which the original temporality in which the relation to the other is situated

as distinct is here, in the scopic dimension, that of the terminal moment. That

which in the identificatory dialectic of the signifier and the spoken will be

projected forward as haste, is here, on the contrary, the end, that which, at

the outset of any new intelligence, will be called the moment of seeing.”17 Arriving at the terminal moment is

the individual viewer’s imperative upon apprehending a work of art. It is

irrelevant to characterize Walter De Maria’s work as sublime, beautiful,

evocative, or thought provoking. Its ability to elicit those experiences can be

asserted as recollections of the subjective moment

of seeing, but not as an explanation of universal (or, even, predictable) experience. The Broken Kilometer, The New York Earth Room, and Time/Timeless/No Time, each have a

strong potential to elicit an admixture of feeling and thought about one’s own

presence. The works do not purport to provide discrete answers or meaning; the

work is essentially epistemological. The only thing determinable about 250

cubic yards of dirt, 500 brass rods, or a 17-ton sphere is a reflexive

confirmation of a subject and object’s presence interacting. In other words,

experiencing the scale first of these works gives way not to objectively

communicable facts, but simply feelings and thoughts about being there.

My response to De Maria’s work is my own, and it cannot invalidate another’s response. While I would not call his work sublime, I can understand the impulse to characterize it as mysterious. But where does that leave us? An essential trait of mystery lies in its ability to induce a compulsion within us to ascertain meaning or knowledge from its circumstance beyond what is immediately apparent. That impulse to always want to know more is the operation through which we confront our mortal limits. And in being there, simultaneously present with the work and at the limits of our own understanding, feeling and thought (thought and feeling) take their own indeterminable course.

Max Mahaffey

Fall 2016

My response to De Maria’s work is my own, and it cannot invalidate another’s response. While I would not call his work sublime, I can understand the impulse to characterize it as mysterious. But where does that leave us? An essential trait of mystery lies in its ability to induce a compulsion within us to ascertain meaning or knowledge from its circumstance beyond what is immediately apparent. That impulse to always want to know more is the operation through which we confront our mortal limits. And in being there, simultaneously present with the work and at the limits of our own understanding, feeling and thought (thought and feeling) take their own indeterminable course.

Max Mahaffey

Fall 2016

17 Lacan, Jacques. "What is a Picture?" In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, by Jacques

Lacan, edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, translated by Alan Sheridan, 105-119. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1977.